This piece is produced by S&P Global Sustainable1, S&P Global's single source of essential sustainability intelligence to navigate the transition to a low carbon, sustainable and equitable future.

Key Takeaways

- Disclosure regulation in the U.S. must strike a balance between the needs of investors and requiring information companies can reliably provide.

- Companies and sectors are at widely varying stages of disclosures on climate change.

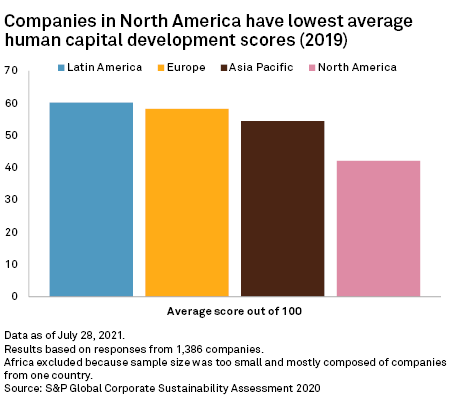

- S&P Global’s 2020 Corporate Sustainability Assessment found North American companies collectively had the lowest average human capital development scores compared to other regions, an indication that more work is needed in this area.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is poised to roll out ESG disclosure regulations on climate risk and human capital management. New rules could plug gaps and inconsistencies in data that many investors have identified as a challenge.

But in crafting these regulations, Wall Street’s top regulator will need to tackle several thorny questions: How should the agency address corporate liability concerns? What specific metrics are needed? And to what extent should the SEC harmonize its disclosure rules with existing voluntary and mandatory standards in other parts of the world?

The SEC is considering several regulations that would enhance ESG disclosures in two key areas: One is climate change — part of the ‘E’ in ESG. The other is human capital management, or the way companies handle their workforce — part of the ‘S’ in ESG.

SEC Chairman Gary Gensler in a July speech at an event held by the Principles for Responsible Investment, or PRI, said: “Investors are looking for consistent, comparable, and decision-useful disclosures so they can put their money in companies that fit their needs.”

Companies are at varying stages in their practices related to human capital management. The S&P Global 2020 Corporate Sustainability Assessment, or CSA, surveyed nearly 1,400 companies around the world on their human capital development practices in 2019, on topics like training, employee development programs and human capital return on investment.

The average score of all those companies in that category was 53 points out of 100. But on a regional basis, North American companies had a lower average score of 42 points, which is an indication that companies in the region have room to improve.

The SEC is also weighing whether to increase the transparency fund managers must provide on products stamped with an ESG-related label, such as ‘sustainable,’ ‘green,’ or ‘low-carbon.’

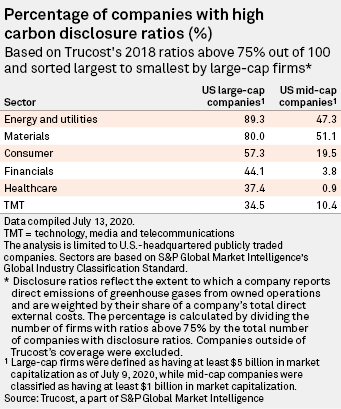

Larger U.S. publicly traded companies tend to be more transparent than smaller ones about their climate risks, and energy, utilities and materials companies generally disclose them more than other industries regardless of their size, a review by S&P Global Market Intelligence of Trucost data found in 2020. Greater transparency by companies on climate risks could further help fund managers in creating and tweaking the composition of ESG-related funds

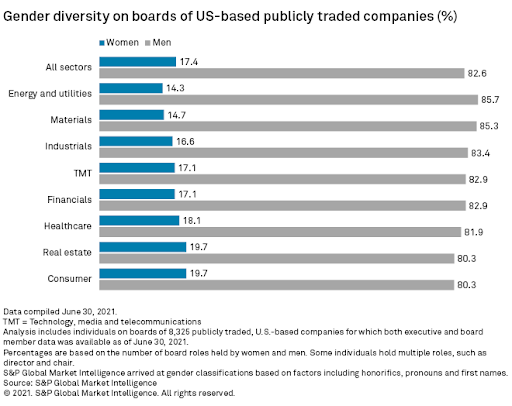

The SEC also may require enhanced disclosures on the diversity of board members and nominees. Gender diversity on U.S. boards remains relatively low. Women held 17.4% of board positions and 20.2% of senior management positions at U.S.-based publicly traded companies as of June 30, according to an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis.

Below, we outline some of the key questions that investors are debating in the U.S. disclosure landscape.

1. What is the appropriate forum to publish new ESG-related disclosures?

Some companies want to continue publishing climate disclosures on their websites instead of via a formal SEC filing. The companies want some kind of protection or safe harbor if it turns out their climate change risk projections, for example, are not accurate.

For his part, Gensler has asked staff to consider whether the agency should make companies provide climate information in form 10-K annual reports.

To understand more about human capital disclosures, listen to this episode of ESG Insider, a podcast from S&P Global Sustainable1

2. Should climate disclosure rules include sector-specific requirements?

Every sector faces a unique set of climate risks and opportunities. Details that may be important to understanding the transition plan away from fossil fuels for the oil sector, for example, may not be so critical when it comes to the climate risks and opportunities for technology companies.

S&P Global’s 2020 annual CSA review of corporate human capital development practices shows that certain sectors are more advanced in their practices than others. The telecommunication services, banks, and food and staples sectors scored the highest in this metric. Retailing, media and entertainment, and healthcare equipment and services had the lowest average scores.

3. When it comes to climate, how do you strike a balance between what investors are seeking and what companies can provide?

Earlier this year, then-Acting SEC Chair Allison Herren Lee sought public comment on whether the agency should go beyond the guidance it issued in 2010 and issue a formal rulemaking — something investors had requested.

In a late-July speech, Gensler said the agency received more than 550 unique comments with three out of every four supporting mandatory disclosures. He noted that investor demand for consistent, comparable climate information from companies has increased in recent years.

“Investors don’t have the ability to compare company disclosures to the degree that they need,” Gensler said. “Companies and investors alike would benefit from clear rules of the road.”

But those rules of the road will not be simple to craft. On climate change, the SEC will need to strike a balance between the information investors want and the information companies can reliably provide. Companies are still learning how to assess many climate-related topics.

One of the SEC’s commissioners, Hester Peirce, has raised questions about whether the agency will be able to achieve consistent ESG reporting by companies. At a July online event hosted by The Brookings Institution, Peirce noted that ESG metrics and methodologies involve a lot of assumptions and that not all stakeholders agree on what those should include.

“We see that even with very standardized financial reporting issues, it's hard to keep issuers hewing to a standard that's comparable across all companies,” Peirce said.

4. How do you strike a balance between qualitative and quantitative climate disclosure?

Another decision the SEC will need to make in the climate disclosure rulemaking is what specific metrics or quantitative data it should require, versus what qualitative information companies should provide as text in the narrative of their reports.

“Qualitative disclosures could answer key questions, such as how the company’s leadership manages climate-related risks and opportunities and how these factors feed into the company’s strategy,” Gensler explained at the July PRI webinar. “Quantitative disclosures could include metrics related to greenhouse gas emissions, financial impacts of climate change, and progress towards climate-related goals” such as net-zero targets.

Gensler has mentioned banking, insurance and transportation as a few of the specific sectors that might be required to provide tailored reporting on climate change.

One set of quantitative metrics the SEC is likely to include are Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Scope 1 emissions are those created by company operations, and Scope 2 emissions are generally those associated with any electricity a company purchases. But Gensler has indicated the agency is still figuring out what to do about Scope 3 indirect emissions, which occur in the supply chain — including when customers use the products or services the companies provide.

Scope 3 emissions are inherently harder to calculate, in part, because they depend on accurate emissions information from suppliers. Some of those suppliers operate in countries without disclosure requirements.

5. How do you harmonize with existing climate standards?

Given that many major companies that are publicly traded on a U.S. exchange also operate on an international scale, the SEC will also need to decide the extent to which it will align or harmonize its climate disclosure requirements with those in other regions and groups.

A number of companies and investors have asked the agency to take outside rules and methodologies into account to avoid creating yet another set of standards in what is becoming a crowded space.

Two non-governmental disclosure regimes, in particular, came up frequently in comments to the SEC. One is the voluntary framework created by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, or TCFD. The other is the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, or SASB, which recently merged with the International Integrated Reporting Council to become the Value Reporting Foundation.

The EU also has a number of environmental and disclosure regulations in the works or that have recently been revamped, including the proposed Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, or CSRD. And the SEC will have to decide the extent to which it wants to align regulations with those standards.

To learn more about CSRD, listen to this episode of ESG Insider, a podcast from S&P Global Sustainable1.

6. Just how do you measure human capital management?

Much less is known about what the SEC might do on human capital management disclosures, although Gensler has listed several potential metrics.

A rulemaking on mandatory human capital disclosures would build "on past agency work and could include a number of metrics, such as workforce turnover, skills and development training, compensation, benefits, workforce demographics including diversity, and health and safety,” Gensler said in a June speech.

The SEC has taken some small steps toward human capital management disclosure in the past. For example, in 2020, the agency required companies to provide human capital management disclosures. But rather than require a specific set of metrics or details from companies, the SEC said companies must decide which metrics, if any, are material enough to report.

Even with this revision, companies were all over the map on what they disclosed. A report by Compensation Advisory Partners in February found human capital disclosures under the rule ranged from as few as 63 words to more than 6,800 words — that largest disclosure came from Wells Fargo in its proxy report.

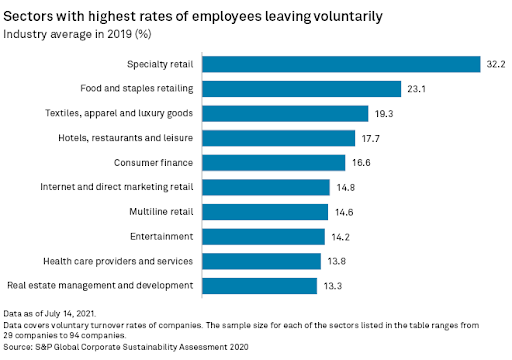

Employee turnover is one area of human capital management investors want to understand. S&P Global’s annual CSA measures both total company turnover and voluntary turnover— that’s when employees leave of their own accord. Voluntary turnover “may reflect high levels of uncertainty or dissatisfaction among employees or structural organizational changes,” the companion guide for companies on the 2020 CSA states.

Voluntary turnover rates can vary greatly among companies and sectors. In the 2020 CSA, which covers company practices for the year 2019, the average turnover rate for sectors ranged from 3% for the automobile industry to 32% for the specialty retail sector. Within the specialty retail sector, the 2019 average voluntary turnover rate among companies reviewed ranged from about 2% to 83%.

As for what human capital metrics investors would like the SEC to include, some have asked for both universal metrics and industry-specific ones.

The Human Capital Management Coalition of 35 institutional investors representing more than $6.6 trillion in assets has asked the agency to require at least four “fundamental metrics:” the number of employees, including full-time, part-time and contingent labor; total cost of the workforce; turnover; and employee diversity and inclusion.

Moving forward, a balanced approach

As the SEC moves forward in the rulemaking process for climate and human capital disclosures, it will need to take a balanced approach that weighs the needs of investors without seeking information companies cannot reliably provide. And the SEC will likely not be done with ESG disclosures with this first set of rules.