The international cargo and container shipping industry plays a central role in global supply chains, but until recently has made few inroads toward decarbonization. That needs to change if the world is going to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Maritime shipping is one of the few sectors left out of the language of the Paris Agreement on climate change. The industry currently accounts for a relatively small share of global CO2 emissions — between 2% and 3% according to S&P Global Platts Analytics — but some scientists have projected that maritime shipping could account for 17% of total annual CO2 emissions by 2050.

Shipping already plays a massive role in the global economy. The public got a stark reminder of that fact when the coronavirus pandemic upended supply chains, and again in March 2021 when a massive container ship blocked the Suez Canal for nearly a week. Seaborne ships on average carry more than 80% of global trade by volume.

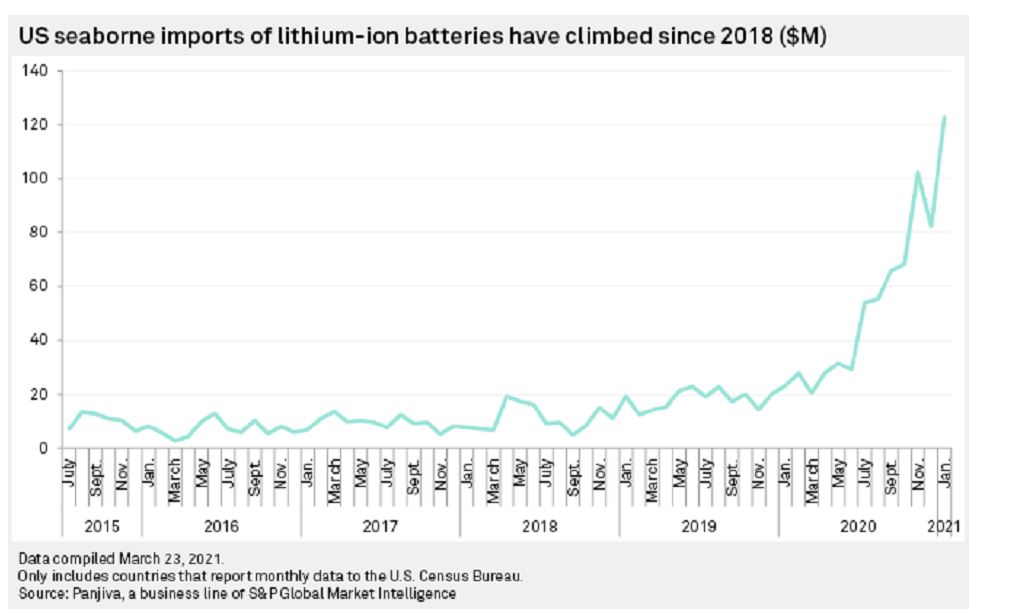

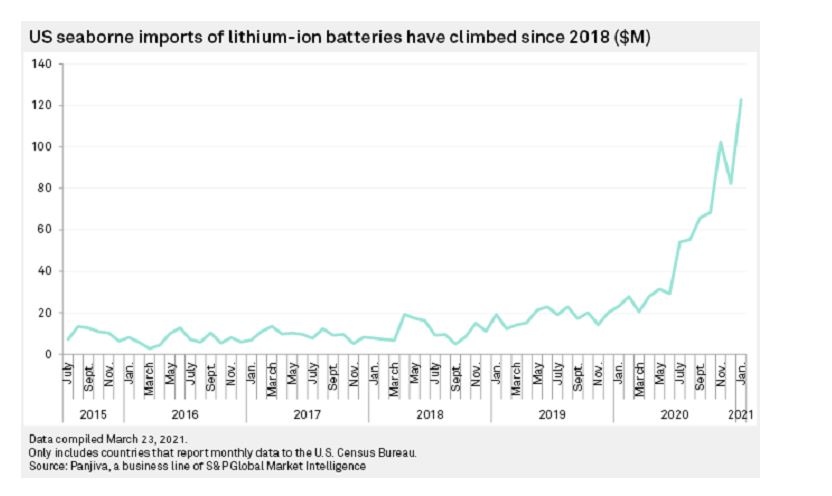

Unless the industry changes course quickly, many supplies that other industries need to support their low-carbon transition — everything from wind turbine blades to lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles — will be transported on cargo and container ships fueled by fossil fuels, known in the industry as marine bunker fuels.

As companies start pursuing their net zero targets, we expect shipping of materials needed for the low-carbon transition to climb. Some, such as lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, have already begun to show an uptick in demand.

Political, regulatory winds are shifting

There is change on the horizon, as regulators, industry groups and financial institutions take steps to steer the shipping sector toward decarbonization. For starters, look to the United Nation’s International Maritime Organization. The IMO is the regulatory agency for the global maritime sector, and it set a goal of halving annual greenhouse gas emissions from maritime shipping by 2050 from 2008 levels. This target still falls short, however, of what scientists have called for to achieve global net zero emissions by 2050.

To support the IMO’s goal, the regulator’s Marine Environment Protection Committee is poised in June to establish new emissions reduction and efficiency requirements for ships that would take effect in 2023.

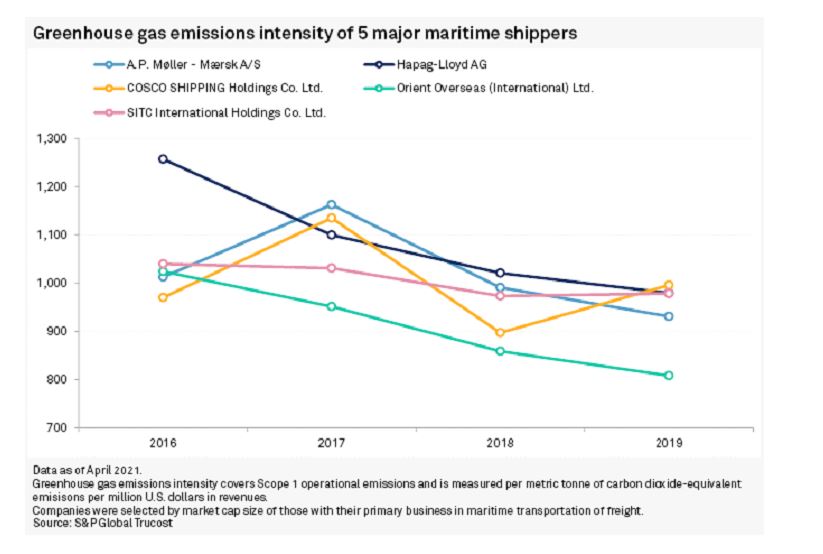

The IMO and others have found that the sector’s emissions intensity has decreased in recent years. But that drop was primarily due to increased ship size, and design and operational improvements such as decreased traveling speed — not the result of switching to lower-carbon fuels, according to an IMO greenhouse gas emissions study published in 2021. Instead, the sector’s annual emissions climbed.

The political winds also appear to be shifting. U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry in April announced the U.S. will join Saudi Arabia as the second of only two countries pledging to work toward the IMO’s greenhouse gas goal. And the European Union is looking to include the shipping industry in its mandatory cap-and-trade carbon market, more commonly known as its emissions trading scheme, as early as 2022, which could push the industry to move faster.

Aligning portfolios with the Paris Agreement

READ MORE >Charting the route

While there are signs of progress, the shipping sector faces some unique challenges. Zero-carbon fuels and technologies are not available at the size, scale or price the industry needs for wide-scale adoption, according to the International Chamber of Shipping, the sector's primary trade association. To create a zero-emissions shipping fleet, “new fuels will need to be developed along with novel propulsion systems, upgraded vessels and an entirely new global refueling network,” the group said in its report.

For a ship to be zero-emissions, it must be capable of operating on fuels or other forms of propulsion that do not emit carbon and other greenhouse gases.

The sector is exploring a range of zero-emissions fuels and technologies, including batteries, sustainable biofuels, and green or blue hydrogen and their derivatives such as ammonia and methanol. Blue hydrogen is produced from natural gas by splitting its molecules into hydrogen and carbon dioxide and capturing and storing the CO2.

Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water through electrolysis and powering the process using renewable electricity sources such as wind and solar.

But zero-carbon fuels alone are still far more expensive than marine bunker fuel oil, even before you bake in the costs of infrastructure changes. For example, Danish chemical company Haldor Topsoe in 2020 forecast that green ammonia produced using solar and wind energy could be priced at $21.50 to $47.70 per gigajoule by 2025 and potentially drop to a range of $13.50 to $15 by 2040. In comparison, fuel oil at the time of the study was priced at a range of $12.50 per gigajoule to $15 per gigajoule.

Regulation is also a challenge. Because shipping is regulated internationally by the IMO, the politics of decarbonizing shipping can be complicated by the fact that countries have varying degrees of interest in pushing for change. While shipping impacts every country in the world through global trade, ports in a handful of countries provide the fuels that account for the lion's share of shipping fuel global emissions.

Path to Net Zero Riddled with Potential Pitfalls

READ MORE >Setting sail for decarbonization

Meanwhile, a number of shipping companies are starting to set their own decarbonization goals that go beyond the IMO’s target. One of the largest shipping companies in the world, A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S, aims to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and has an interim target of a 60% reduction by 2030.

Maersk in March pledged to launch the first carbon-neutral vessel by 2023 and has said it will launch its first zero-carbon emissions vessel by 2030. Morten Bo Christiansen, head of decarbonization at Maersk, in March told S&P Global Platts that it is reading the tea leaves on where its customers are headed.

"Our perspective is five or 10 years from now, it will be unacceptable to many of our customers to have that carbon footprint in their global supply chain. So we really see this as a strategic imperative to solve this problem," Christiansen said.

Lenders are also taking note. As of December 2020, more than 20 financial institutions that collectively represent over US$150 billion in loans to the shipping industry — or more than a third of global shipping finance — were signatories to the Poseidon Principles. That’s a global framework for assessing and disclosing the climate alignment of financial institutions' shipping portfolios.

An inaugural report released late last year showed that shipping portfolios aligned with the climate goals set by the IMO at only three of 15 disclosing institutions: Dutch bank ING Groep NV, French export credit agency Bpifrance Assurance Export, and Eksportkreditt Norge AS, also known as Export Credit Norway.

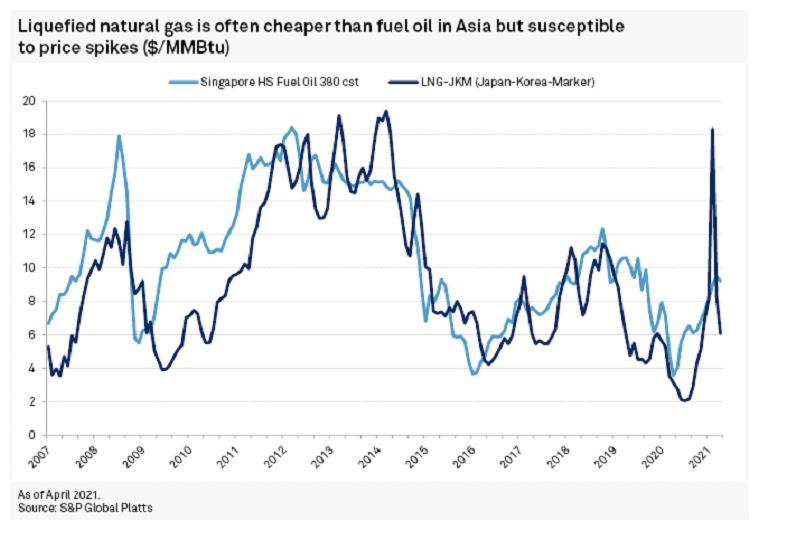

But even as it pursues deep decarbonization pathways, the maritime shipping industry is taking up interim solutions. For starters, some shippers have begun using liquified natural gas as a shipping fuel, which produces significantly less carbon than the oil the industry uses.

Furthermore, natural gas in its liquified form, or LNG, is often less expensive than fuel oil, although the LNG is susceptible to price spikes due to changes in weather and logistical constraints.

But since natural gas is not viewed as a permanent solution because it still emits carbon, the industry is pursuing zero-carbon options as well. The Global Maritime Forum recently found that the number of pilot projects around the world increased in 2020 to 106 from 66, focusing on ship technologies, fuel production as well as bunkering and recharging facilities.

Carbon Offsets Prove Risky Business For Net Zero Targets

READ MORE >Getting past the tipping point

To achieve the IMO's goals, the industry also needs commercially viable zero-emissions vessels to start entering the global fleet by 2030, and the number of those ships must quickly increase over the following 10 years. Making that possible will also require getting to the stage of adoption where zero-emissions fuel costs start coming down, Jesse Fahnestock, project director at the Global Maritime Forum, said in an interview.

More than 140 companies in the maritime, energy, infrastructure and finance sectors are participating in the Getting to Zero Coalition, which is coordinated by the Global Maritime Forum. The coalition recently released a report that found getting past the tipping point for zero-emissions fuel costs will require the industry to have 5% adoption of those fuels by 2030, with adoption ramping up to more than 90% by the mid-2040s. The tipping point for the shipping industry would be when low-carbon technology costs decline enough to prompt its rapid adoption "with positive feedback loops between different actors raising confidence, increasing demand and investment throughout the value chain," the Getting to Zero Coalition explained.

The coalition believes that 5% adoption by 2030 is "a point from which you have enough fuel production and enough zero-emissions vessels in place that you could feasibly have a fast roll-out after that in the way that we've seen...happen with renewable energy," said Fahnestock.

This piece was published by S&P Global Sustainable1 and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global. S&P Global Platts and Eklavya Gupte contributed to this article.