The Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) FASB accounting standard update[1] requires institutions to estimate future expected credit losses (ECLs) when calculating provisions for investment portfolios. This policy was a widely debated topic even before the COVID-19 crisis. After facing significant challenges in terms of data availability, modeling, and reporting, many public entities began to apply this standard as of January 1, 2020. However, new challenges and questions are arising as we face uncertainty resulting from economic disruptions caused by the pandemic.

While CECL does not require a specific method to determine the allowance for credit losses, the information considered to estimate ECLs includes the borrower’s creditworthiness and changes expected within the current and forecasted economic and business environment.

A number of important new challenges related to CECL estimation arose during this crisis, requiring additional considerations when calculating ECLs during this uncertain time. We touch on three of these in this article:

1. Borrower’s creditworthiness deterioration

2. Swift changes in current and forecasted economic and business environment

3. Impact on allowance estimates

1. Factoring Changes in a Borrower’s Creditworthiness

COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on many industries, including travel, hospitality, construction, oil and gas, and restaurants. Since credit ratings are the primary measure of creditworthiness and also an important component of a portfolio ECL, reflecting the damage and predicting the long-term impact the downturn will have on borrower ratings will be crucial for CECL estimation.

Since ratings systems are struggling to catch up with the current changes, credit ratings may not have been updated to reflect current conditions. In addition, institutions may be using an increased level of judgment in evaluating a borrower’s creditworthiness.

Two different approaches can be taken to evaluate the impact of changes in the business cycle when assigning credit ratings to borrowers. One is a point-in-time system (PIT) where risks are evaluated based on the current condition of a firm regardless of the phase of the business cycle at the time of evaluation. In a PIT rating system, grades will aim to reflect the business cycle and ratings tend to change more frequently - being upgraded during economic upturns and downgraded at economic downturns. Importantly, ‘ex-post’ default rates per grade remain stable regardless of the business cycle.

The other approach is a through-the-cycle system (TTC), where assessments have taken into account an assumption that a firm is experiencing stress that is typical for the bottom of the business cycle. In a TTC rating, borrower grades tend to remain the same through the business cycle, while ‘ex-post’ default rates within the same grade fluctuate reflecting the business cycle.

Both of these rating system types are being significantly challenged by the current crisis and need to remain current, either through using rating changes or through using changes in default rates per credit rating grade.

At S&P Global Market Intelligence (‘Market Intelligence’), we find that when developing an estimate of ECL on financial assets under the current circumstances, gauging for an adequate response to the swift economic changes requires a combination of the two types of ratings - TTC assessment with PIT - as well as macro-conditioned prospective adjustments. Our ECL methodology starts from the public rating (or Market Intelligence Scorecard equivalent score) of a borrower before assigning a TTC Probability of Default (PD) term structure. These TTC PDs are based on long-term historical average observed default rates by rating grade and are subsequently adjusted using the most current market data and relevant sector-specific macroeconomic forecasts[2].

In addition to adjusting the default rates to be reflective of the macroeconomic current and forecast conditions, for ECL estimation purposes, the stable borrower rating grades themselves may merit and adjustment up or down to reflect the swift impact of the crisis. This might occur if and when the rating grades are not caught up with long-term changes in industry fundamentals, and the assumptions of the typical stress at the bottom of the business cycle for the specific industry. The aforementioned situation is exacerbated by the impact of the COVID-19 recession, which looks very different from a broad downturn scenario typically modelled for CECL, with severe stresses on certain industries (such as travel, hospitality), milder, region-specific or even positive impacts on other industries (such as certain retail segments, technology and digital communication). For this reason, the Market Intelligence CECL model may apply additional PIT adjustments[3] to the TTC borrower ratings – a model application feature becoming more common during the pandemic, ensuring ratings are reflective of current industry-specific conditions.

It is important to note that, while industry-specific adjustments and reviews remain a key part of keeping a borrower’s rating current during times of crisis, this does not in any way minimize the need for a robust fundamental risk rating methodology and a borrower-specific risk factor review. Some borrowers may struggle for an extensive period during and post-crisis, while other borrowers, even in the hardest hit areas may be able to keep making payments. The key questions that need to be answered during a crisis in order to differentiate between borrower prospects may require a qualitative as well as quantitative review of a robust set of industry-specific borrower risk factors and metrics. For example, Market Intelligence Credit Risk Assessment Scorecards offer a robust default and facility-specific recovery estimation using both a quantitative and qualitative risk factor analysis. The latter are key to forming a credit risk view reflective of the current crisis and post-crisis recovery prospects, including:

- Changes in industry risk fundamentals

- Changes in the business environment

- Changes in borrower’s liquidity and financial flexibility. A key question to consider, how long will a borrower’s resources last if current economic conditions persist or worsen?

- Diversification effects: If borrowers have various operating segments, it may help to consider performance across all segments. For example, while a borrower may perform poorly in one segment, its operations in other segments may cushion against negative effects of the poorly performing sector

2. Factoring Swift Changes in Economic and Business Environment

To estimate credit losses, an entity must consider both the current and forecasted direction of the economic and business environment. Under CECL, this includes consideration of historical loss information and making adjustments for current events and reasonable and supportable forecasts. But since the pandemic is an unprecedented event, what is considered a ‘reasonable and supportable’ forecast will likely have a very high level of uncertainty around it and frequent updates of the forecast will be necessary. S&P Global Ratings acknowledges a high degree of uncertainty about the evolution of the coronavirus pandemic[4] and its impact on macroeconomic forecasts. Uncertainties such as how long the pandemic will last, how fast the economy can recover, as well as the government’s response and benefit from stimulus packages are difficult to factor into a forecast.

What we do know is that the financial markets reacted swiftly to COVID-19 pandemic, with the S&P 500 Index losing around 30 percent since its peak in February, 2020. The U.S. entered recession in March 2020, ending the longest expansion (128 months) in the country's history. On the bright side, the current assumption is that the recovery has already begun, which means that this would also be the shortest recession on record. According to the end of Q2 2020 forecast of S&P Global Economics[5], we can expect third-quarter GDP to grow 22.2% (quarter over quarter) after falling almost 35% in the second quarter. S&P Global Economics now expect the unemployment rate to decline to 10.9% in the third quarter and a somewhat slower drift down for the unemployment rate later this year, falling to 8.9% in the fourth quarter5.

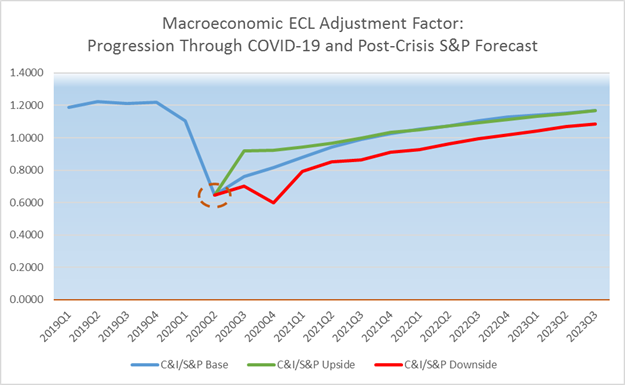

This forecast is also reflected in our CECL model, which relies on a macroeconomic forecast from S&P Global Economics of the Market Indices as well as macroeconomic variables. Our Commercial and Industrial (C&I) CECL model uses factors that have been shown to be most indicative of changes in C&I default and loss rates, such as GDP growth, Unemployment rate, BBB spread as well as housing and equity indices. The forecasted paths of these variables (updated every quarter by S&P Global Economics) are used within our CECL model to derive an adjustment factor (‘Z-factor[6]’) applied to the remaining term structure of historical PD/Loss Given Default (LGD) rates of individual instruments. Each quarter, S&P Global Economics projected two scenarios in addition to their base case, one with faster growth than the baseline and one with slower (Chart 1).

Source: CECL Model for C&I, S&P Global Market Intelligence, September 2020. For illustrative purposes only.

As can be observed from the chart above, the good news for the U.S. economy is that the recession may have ended as fast as it started, with a bottom in the second quarter likely recorded in May. The bad news is that the recovery will be slow for some sectors. For example, while consumers may be permitted to fly, ongoing and uncertain restrictions and the loss of confidence by passengers will likely keep air travel below 2019 utilization levels through 2023.[7]

3. Estimating Allowance Impact

What do such wild swings in the Economic and Business Environment reflected in the macroeconomic data and forecasts mean for an Allowance Estimate from our CECL model?

The timing of an economic turnaround and the resulting impact on lifetime ECLs and corresponding allowance is reflected in our asset-specific CECL model using the Z-factor shaped by our macroeconomic forecast. Our analysis suggests that CECL allowances related to (C&I) corporate exposures for a sample portfolio would significantly increase, when the severe downturn in macroeconomic indicators and economic scenarios are fully factored into CECL estimates. In addition, we can expect the allowance estimate (before any qualitative adjustments to account for forecast and model uncertainties) to stay elevated until a full recovery and a neutral economic environment is achieved. A neutral/average economic and business environment is indicated when our model Z-factor reaches back to the 1.0 level which is currently forecasted in Q4 2021 – Chart 1.

When we compare the baseline scenario allowance estimation level for a sample[8] C&I portfolio made in Q2 2020 which incorporates the COVID-19 impact, to the estimate from Q1 2020 which still did not incorporate the COVID-19 impact, our CECL model suggested that the cumulative expected losses will be almost doubling (Chart 2), from 1.06% to 2.03%.

Source: CECL Model for C&I, S&P Global Market Intelligence, data as of May 1, 2020. For illustrative purposes only.

Thus, financial institutions should frequently assess the economic impact of various economic recovery scenarios as well as impact on existing portfolio credit ratings by using their own (or benchmark) credit risk assessment and CECL models with reliable updated forecasts.

[1] FASB Accounting Standards Update No. 2016-13, Financial Instruments, Credit Losses (Topic 326)

[2] Forecasts from S&P Global Ratings; Alternatively, the model can also “ingest” internal forecasts for any of the required macroeconomic factors.

[3] The industry-specific PIT adjustment draws on Market Intelligence’s quantitative PD Market Signal Model which calculates a daily PD for all publicly listed corporates.

[4]S&P Global Ratings, “COVID-19 Heat Map: Post-Crisis Credit Recovery Could Take To 2022 And Beyond For Some Sectors”; June 24, 2020

[5] S&P Global Ratings, “The U.S. Faces A Longer And Slower Climb From The Bottom”; June 25, 2020

[6] The Z-factor is defined in a way that a value greater than 1 arises if a set of predicted macroeconomic factors for future period indicate a PD% that is lower (more benign) than the long-term average PD rate. Likewise, a Z-factor less than 1 arises if a predicted economic environment indicates a PD that is greater than the average historical PD rate.

[7] S&P Global Ratings, COVID-19 Heat Map: Post-Crisis Credit Recovery Could Take To 2022 And Beyond For Some Sectors; June 24, 2020

[8] We created a fictitious portfolio using the S&P Global Ratings 2019 Annual U.S. Corporate Default And Rating Transition Study as a guide; since U.S. accounts for the majority of the speculative-grade issuers and median issuer is in the B rating category. Additional assumptions included an initial average remaining term of 2.2 years, and instrument type as loans, secured by all assets.