Denmark's Ørsted owns the first offshore wind project in the U.S., the 30-MW Block Island wind farm. |

BP PLC became the latest company to enter the fray in September, when it bought into two offshore wind developments owned by Norway's Equinor ASA, the Beacon Wind and Empire Wind projects, which between them have development potential of 4,400 MW, including an 816-MW state contract already awarded for Empire Wind. The joint venture between the two oil and gas firms follows a host of deals and leasing rounds that have seen the major players of Europe's own offshore boom take the lead in the sector's next big market.

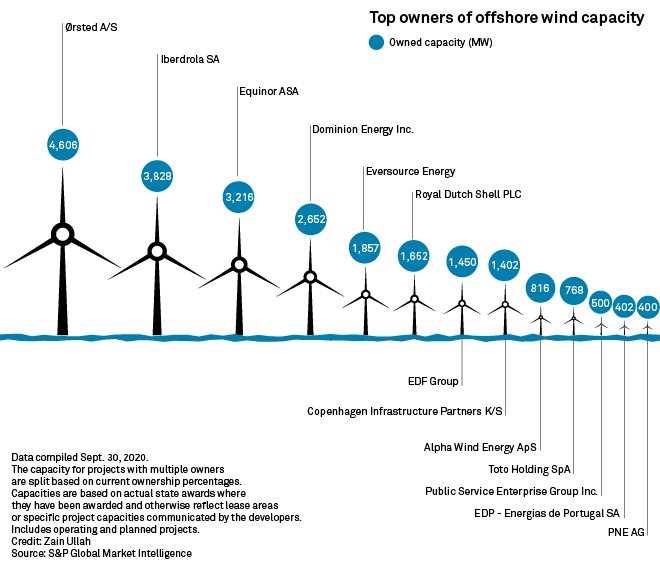

Denmark's Ørsted A/S, Spain's Iberdrola SA and the BP-Equinor joint venture now own just over 11,600 MW of planned projects along the coast, while Dominion Energy Inc. and Eversource Energy — the next two top owners — are sitting on a combined 4,500 MW of projects, according to an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis.

Between them, the two U.S.-based companies own less planned capacity than global market leader Ørsted alone and, aside from Public Service Enterprise Group Inc., there are only a handful of other U.S. companies involved in several early-stage projects — making up a small slice of the more than 20,000 MW of projects already announced or under development.

While project capacities are subject to change as developers bid into different state auctions, an undeniable trend is emerging: With energy and power giants from Denmark, Spain, Norway and the U.K. crowding out inexperienced domestic developers, the U.S. offshore wind market will be far from American-made.

"They are more playing second fiddle to the large international partners," Deepa Venkateswaran, an analyst covering European utilities at Alliance Bernstein, said of the U.S. companies involved. "It's a very different landscape to onshore wind and solar."

And as states keep increasing offshore wind targets and take steps to solicit more projects, the outsized foreign influence has served to raise political risks for developers looking to convince American lawmakers that the blossoming market will be a boon to U.S. industry.

That has given ammunition to opponents of offshore wind projects, especially commercial fishing interests whose coordinated opposition helped stall a decision by the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management on whether to approve the proposed 800-MW Vineyard Offshore Wind Project. That project, which could be the first utility-scale offshore wind farm in federal waters, is a joint venture of Denmark-based Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners K/S and Avangrid Renewables LLC, a subsidiary of Iberdrola-owned Avangrid Inc.

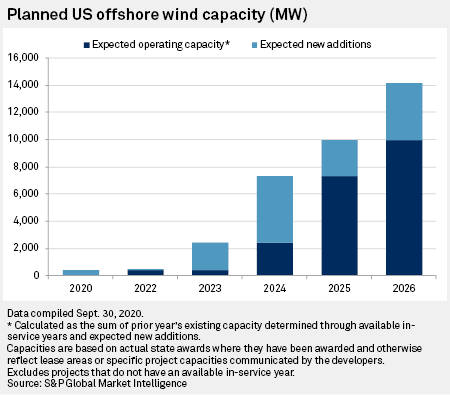

Brandon Burke, policy and outreach director for the Business Network for Offshore Wind, noted that states are looking to develop just under 30,000 MW of offshore wind capacity by 2035 — more than Europe has installed over the last three decades. So it makes sense for American companies to partner with Europeans with more experience, as Dominion, Eversource and PSEG have all done.

Still, Burke said that during a quickly accelerating energy transition, American companies — particularly domestic oil and gas majors, which have decades of experience in building offshore infrastructure — are missing out on a chance to diversify.

"It really is a huge opportunity, really a once-in-a-generation opportunity, to build an industry," Burke said.

'Putting your eggs in many baskets'

While the majority of planned U.S. offshore wind capacity is in the hands of European developers, the industry has to date been defined by partnerships and joint ventures. That includes all three of the largest U.S. players, who have each linked up with Ørsted for their initial projects.

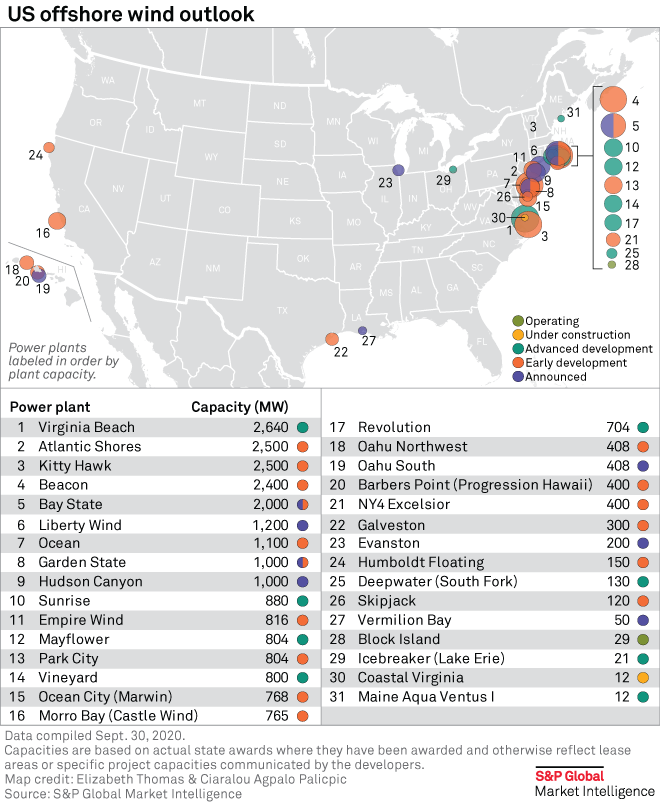

The Danish company just completed the 12-MW Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind Pilot Project with Dominion — only the second offshore wind farm to be completed in U.S. waters, which Dominion plans to chase with the 2,600-MW Virginia Beach Offshore Wind project, to be built in three phases between 2024 and 2026. By building the smaller plant for Dominion, Ørsted reserved the exclusive right to negotiate a stake in the Virginia Beach project, too.

The pilot project underscored the lack of a real U.S. supply chain for offshore wind projects. To get around the Jones Act, which prohibits foreign vessels from transporting goods between U.S. ports, the material for the wind farm was manufactured in Europe and shipped to Halifax in Nova Scotia, from where it was delivered to the project site. Dominion is now investing in a Jones Act-compliant ship, and Ørsted and Eversource have also inked a deal to build one. European companies are also participating in capacity auctions to invest in U.S. port infrastructure.

"That's why we're working to really develop that U.S.-based supply chain and this installation vessel is one of those steps," said Jeremy Slayton, a Dominion spokesperson.

Ørsted is also jointly developing one project with PSEG in New Jersey, the Garden State Offshore Wind Farm, and four large-scale offshore projects with Eversource — the Bay State Offshore Wind, South Fork Wind Farm, Revolution Wind Offshore and Sunrise Wind Offshore Farm projects.

Ørsted declined a request for an interview for this story. But Michael Ausere, vice president for business development at Eversource, said that in 2015, the company began noticing the falling prices of offshore wind in Europe and found a natural partner in the Danish utility.

"We're talking about building a generation resource in a marine environment, and that's not something we've done before," he said. As important as Ørsted's experience in building offshore wind farms was its knowledge of the costs involved, he added.

Grzegorz Gorski, COO of Ocean Winds, the joint venture company founded last year by EDP Renováveis SA and Engie SA to pool their offshore wind operations, said risk-sharing partnerships are a necessity in offshore wind, where the cost of a single project can run into the billions of dollars.

"It's about putting your eggs in many baskets," Gorski said.

Ocean Winds is developing the Mayflower Wind Offshore Project with Royal Dutch Shell PLC off Massachusetts, where its lease area can support up to 1,600 MW of capacity, and already co-owns offshore projects with companies including Mitsubishi Corp., Sumitomo Corp. and Repsol SA in Europe. In the U.S., Gorski said seabed leases are already so expensive that risk-sharing is even more important. Leases have so far run up to $135 million, in addition to rent payments, and prices are expected to rise further in future auctions.

"It's a nice chunk of money, and you are years away from [a final investment decision] — without the guarantees that you will actually reach it," Gorski said. "Because of this, it's better to have half of one project than one project."

Ocean Winds' risk-sharing approach has been mirrored by others, said Meike Becker, another Bernstein analyst: Aside from BP and Equinor, Avangrid has brought in financial investor Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners on two of its projects, Vineyard Wind and Park City Wind Offshore, making the Danish investment firm another major player in the U.S. sector.

'We don't have a religion about joint ventures'

While Ørsted's approach has been to partner up with local utilities to break into the U.S. market, Becker said Iberdrola has a built-in advantage through Avangrid, its subsidiary, while EDPR and Engie already have substantial onshore operations in the country.

"These guys are actually very familiar with the U.S. So they're just sticking to their home market," she said.

|

Eric Thumma, Avangrid's interim head of offshore wind, said the company has been able to combine Iberdrola's experience in bringing projects all the way into operation with its own expertise on the U.S. market, pointing to a mutually beneficial relationship likely also envisioned by companies like Ørsted and Eversource.

In the future, Thumma said Avangrid could decide to pursue more projects on its own. The company already has another project announced without partners attached, the Kitty Hawk Offshore Wind Farm in North Carolina.

"Whether we do it with partners or alone is really going to be case by case, examining those specific lease auctions and where the market is going," Thumma said.

Others are similarly non-committal.

"We don't have a religion about joint ventures," said Dev Sanyal, BP's executive vice-president for gas and low carbon energy. "We look at companies and partners and, if there is a natural fit ... we do it."

'A huge market on paper'

Industry observers say BP paid a steep price for its entry deal with Equinor, which cost the company $1.1 billion and, aside from the two projects in New York and Massachusetts, also includes the possibility of additional developments. Other companies looking to get in might also be willing to pay a premium, given the scale and security promised by the market in the long term.

"You can see they wanted an entry into this market, so they paid a pretty high price, given the projects are not yet constructed," said Bernstein's Venkateswaran. "That might be reflected in the prices people are ready to pay [going forward]."

Sanyal said that getting access to land was an important factor in the company's decision to partner up with Equinor — one of only a handful of companies to have already secured seabed rights. The last lease auction was held nearly two years ago and the industry is itching for more. A Bureau of Ocean Energy Management spokesman told S&P Global Market Intelligence that the agency is in "planning stages for additional wind energy areas in the Gulf of Maine, the New York Bight, offshore the Carolinas, California and Hawaii."

"It's a huge market on paper, but not that easy to capture it if you don't have a lease," Venkateswaran said. "So people sitting on top of land have an advantage."

Sanyal said he expects the market to get "a lot more competitive," given the attractive fundamentals. Companies that have yet to make a splash along the U.S. coastline but could be tempted to take a stake include European offshore heavyweights like RWE AG and oil major Total SE, as well as unlisted U.S. investors like Berkshire Hathaway Energy, according to Bernstein.

More West Coast centric developers could also join the fray as development areas expand, said Avangrid's Thumma.

"It's conceivable to see a few more players come into the field, particularly as the geographic focus changes," Thumma said. But he added that the significant entry hurdles of offshore wind would nonetheless limit the number of players, suggesting that the lines have been drawn to a large extent.

"You have to have some financial wherewithal to be in this market," he said.