| Russian President Vladimir Putin's war in Ukraine has diminished foreign private equity's already small presence in Russia even further. Source: Getty Images |

The exodus of most of the world's private capital from Russia in the year since it invaded Ukraine has created long-term liabilities for Russia, undermining aspirations for innovation and diversification of its commodity-centric economy.

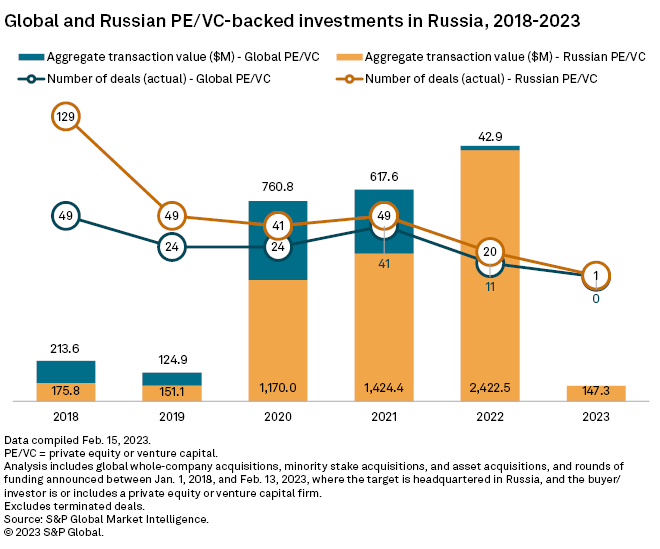

In 2022, the value of investment in Russian companies by nondomestic private equity and venture capital firms plunged 93.1% year over year to just $42.9 million, the lowest in at least five years, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data.

|

Coupled with an array of international sanctions that are prompting skilled workers to flee and limiting Russia's access to economically important technologies, the consequences of the war have been a big step back for "an economy that desperately needs modernization," said Lilit Gevorgyan, a Russia analyst for S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"Russia is actually going to see a reversal of the economic changes it was aspiring to," Gevorgyan said. "It was trying to move away from being a commodity-based economy, but now it's most likely going to go the other way again, which is bad for the country because it will become more vulnerable to commodity market price volatility."

Investors back out

It was not long after Russian President Vladimir Putin sent the initial wave of troops in military vehicles over the border into Ukraine that elected officials in multiple U.S. states began calling for public employee pension funds to divest their Russian assets, which for some is an ongoing process.

U.S. state employee retirement funds with exposure to Russia typically had a very small investment compared with their billion-dollar portfolios, said Alex Brown, research manager for the National Association of State Retirement Administrators. Nonetheless, there was a widespread movement to divest that was made difficult because the assets had lost significant value, "and divesting of those assets immediately wouldn't satisfy a standard of prudence," he said.

By the end of December 2022, Russia had four institutional investor-involved deals with a disclosed value of $190 million, the lowest amount in the past five years, according to Market Intelligence data. All four closed in either January or early February that year, just before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Remaining institutions with disclosed exposure to Russian assets are limited to the sovereign wealth funds of Russia, Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

"Russia desperately needs international investment and capital, but as long as Putin is there, nobody wants to invest in Russia," according to Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, founder of the Chief Executive Leadership Institute at Yale, who, together with CELI Research Director Steven Tian, has compiled a list of more than 1,000 companies that cut back activities in Russia beyond the minimum requirements of international sanctions.

Private equity refocuses

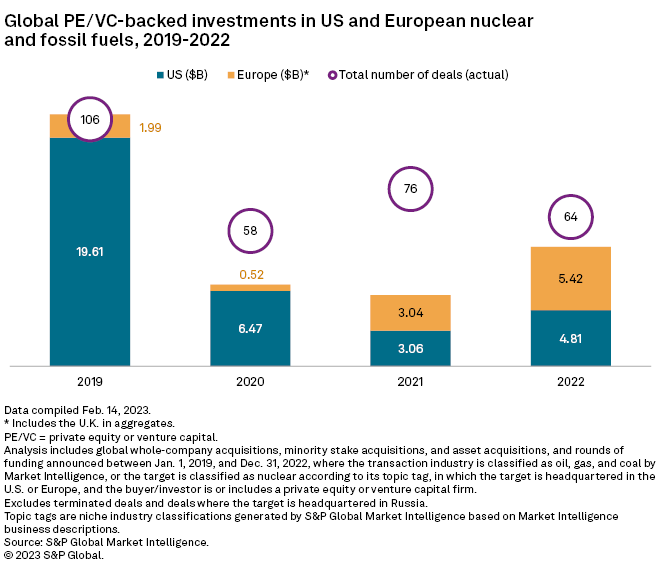

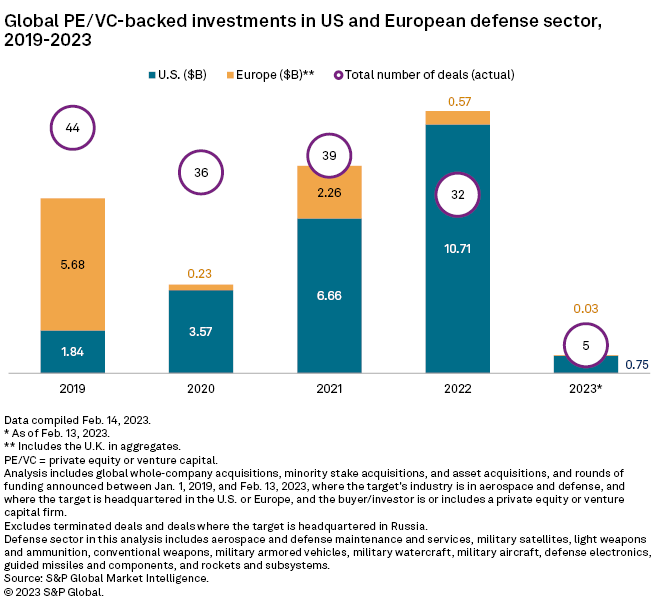

Concurrent with the divestitures, the war in Ukraine has focused private capital on opportunities created by the destabilizing effects of the war. This is especially true for the defense sector of the primary provider of military assistance, the U.S., as well as the European energy sector as Europe weans itself off Russian fossil fuels and returns to energy sources it had previously rejected.

Investment in fossil fuels and nuclear energy companies has been much more evenly distributed between the U.S. and Europe over the last two years, and in 2021 and 2022 more than half of the private equity investments in fossil fuels and nuclear went to projects in Europe.

Of the past four years, private equity investments in European nuclear and fossil fuels companies were at their highest level in 2022, totaling $5.42 billion.

In the U.S. defense sector, private equity investments totaled $10.71 billion in 2022, a higher annual total than any of the previous three years.

Long-term consequences

The newly erected barriers between Russia and global private equity and venture capital firms block a source of risk capital for nascent industries and shrink the ecosystem of international connections and expertise that nurture fledgling innovative companies.

Sanctions and the prospect of conscription into the army have also been considerations of local technical talent. Before the war, Russian IT companies often domiciled in the U.S. or Europe while still paying teams of developers in Russia, said Renat Khairullin, accelerator director for venture capital firm Starta Ventures.

When waves of sanctions hit, making it difficult to pay Russia-based teams and restricting their access to software and some technology, founders relocated their workforce to countries such as Turkey, Georgia and Kazakhstan, Khairullin said.

"[M]aybe 90% of those people, they wouldn't go back [to Russia]. It's too risky," he added.

Western private equity firms seek a degree of stability. Sonnenfeld added that the extended time horizon of private equity investments, up to a decade, prompts firms to seek a "steady, predictable" political environment, which arguably did not exist in Russia even before the war.

Gevorgyan said private equity investors would want a clear view on sanctions before entering Russia, and at this point it appears they will remain in place until there is new leadership in Moscow and a reset of relations with the West.

"[S]ome investors might try to find a backdoor for investment, but those risk-takers will not be from the West," she said.

To learn more about how the war has affected different markets and sectors sign up for a demo of S&P Capital IQ Pro