To listen to some CEOs, the global work-from-home experiment has been nothing short of an overwhelming success.

"We've seen a 41% increase in overall productivity, a 20% increase in internal collaboration time and, interestingly, a 19% increase in external meeting time," The Unilever Group CEO Alan Jope proclaimed on the company’s second-quarter earnings call. "And I think as a result of all of that, we've seen record levels of employee engagement. In fact, our employee well-being score is up by 14%."

Research also suggests that the majority of workers are coping well with the changes. About 75% of employees said they have been be able to maintain or improve productivity on individual tasks, such as analyzing data or writing presentations, since the pandemic began, according to a Boston Consulting Group survey of workers in the U.S., Germany and India, released Aug. 11.

Dig below the surface, though, and there is increasing evidence that while most people are delivering from the home office, it is taking a toll on them emotionally, as interpersonal contact diminishes and the pandemic recession builds anxiety about job insecurity. There is also a reasonable probability that some of the productivity gains being measured by employers do not actually exist.

The issue of remote-working productivity has come rapidly into focus as companies look to make decisions about how to structure their businesses, including their physical footprint, in light of a pandemic that looks set to keep millions of white-collar workers at home at least into next year.

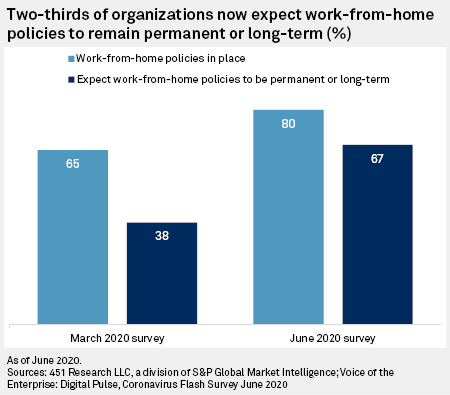

In a March survey by 451 Research, just as the pandemic was causing the first round of lockdowns in the U.S., about one-third of companies saw remote work as a permanent change, but that number jumped to roughly two-thirds when the question was asked again in June.

Research by 451 also found that only 11% of employees felt more productive and more engaged with remote work than work from the office. These positive respondents tended to be more senior within a company, had prior experience with remote work, and were generally more tech-savvy, said Chris Marsh, a principal research analyst with 451, a division of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

About 35% of workers surveyed said they felt more productive but not more engaged, stating that they were struggling with anxiety, not feeling focused and a lack of alignment with their work team. Roughly 55% said they were both less productive and less engaged working from home.

"You see some narratives that say, 'Remote work is great, there's less commute time, people are better off,' but I think the reality is actually it's a minority who feel this is better than pre-crisis," Marsh said.

Workers surveyed said they were anxious about furloughs; the loss of face-to-face contact during the workday; and a sharp increase in calls, meetings and formal messaging. "What we saw pre-crisis was people spending too much time in email, too much time in messaging tools, too much time in video conferencing," Marsh said. "Since the pandemic, it’s just been even more of that."

Productivity illusion

Adding to the murkiness, the new productivity figures may not be tracking true changes in how effective office workers are.

"Productivity is an interesting construct, because for so much of white-collar work, what exactly do you measure for that?" Jerry Davis, a professor of management and organizations at the University of Michigan, said in an interview. "If you’re home all day sewing sweaters, it's pretty easy to measure that. But if you're in consulting … it can be much trickier to get at that."

Some business models are better suited to remote work than others. GitLab, a software company that has no physical office location, has well-defined and easily measurable parameters for productivity.

"They say productivity is not how many hours you stare at a computer screen or how many meetings or calls you attend," said Prithwiraj Choudhury, an associate professor at Harvard Business School. "It is how many sales you make, how many lines of code you finish. It's entirely output-based. So if you do that, you have to trust people that they're going to get it done."

One element of office culture that has been lost during the pandemic is informal collaboration, which has been replaced by new metrics that could be used for productivity measurement.

"The kind of impromptu meetings that you would’ve done just by yelling over the cubicle, stopping by or bumping into someone at the coffee machine; all of that informal stuff now needs to be done formally, and it leaves a trail," said University of Michigan’s Davis.

A chat in the hallway before or after a larger team meeting has now been replaced by an hour-long Zoom call, which would count toward productivity metrics in a way the informal chat would not, even if they achieved similar results, Davis noted.

Pandemic stress

Once the economic situation stabilizes and schools reopen permanently, much of the stress currently attributed to home working may dissipate, and workplaces that maintain work-location flexibility may see lasting benefits.

Research published by Harvard’s Choudhury before the pandemic showed that a 2012 program that allowed patent examiners at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to work from anywhere led to an increase in productivity of 4.4%.

"Moving to your favorite location makes people more motivated to exert more effort," Choudhury said. "If you want to live in Florida and you're a patent examiner, there’s not too many jobs in Florida, so once you get that flexibility … that flexibility is going to be a major boost to productivity."

But for many remote workers in the pandemic age, the transition has been hasty and involuntary, clouding the outlook for future productivity.

"There is this big bulk of people who are just struggling," said 451's Marsh. "I think that, in aggregate, the reality is this is far more painful than it is positive.”