Global semiconductor and electrical steel shortages will continue into 2022, forcing automakers to limit production and pivot away from longtime assumptions such as lean inventories and just-in-time manufacturing.

The supply chain issues in automotive are unprecedented. Consumers have to wait longer and be less picky when choosing vehicles and accept that there are certain features that may not be available due to the chip shortage. This globally synchronized, supply-led disruption is something that has never happened in the modern history of the automotive industry—--in other words, a supply-led environment in which consumers cannot obtain vehicles on a global basis because of limitations on manufacturing inputs.

If the question is whether this gets fixed right away, the answer is no. Whilst the one-off chip shortage shock is largely in control, the underlying disruption is expected to continue for some time. The shortage is widespread because of the different semiconductor families that are impacted. The issue started, for example, with microcontrollers, which is a specific chip family, then moved into cross-chip manufacturing operations, particularly in Malaysia, which meant that several chip types were impacted. And as we look out into 2022, we think that analog chips will be another area of a big concern, thus indicating a further semiconductor product family is expected to experience some disruption.

With regard to the chip shortage, it would be safe to say 2022 is already something of a write off—in other words, disruption will continue. We’re looking at semiconductor lead times that normally would be in the region of 12 weeks having shot up to 26 weeks or more with the prospect of an elongated lead time through 2022. As a function of this, automakers will be called upon to make trade-offs when producing vehicles in 2022.

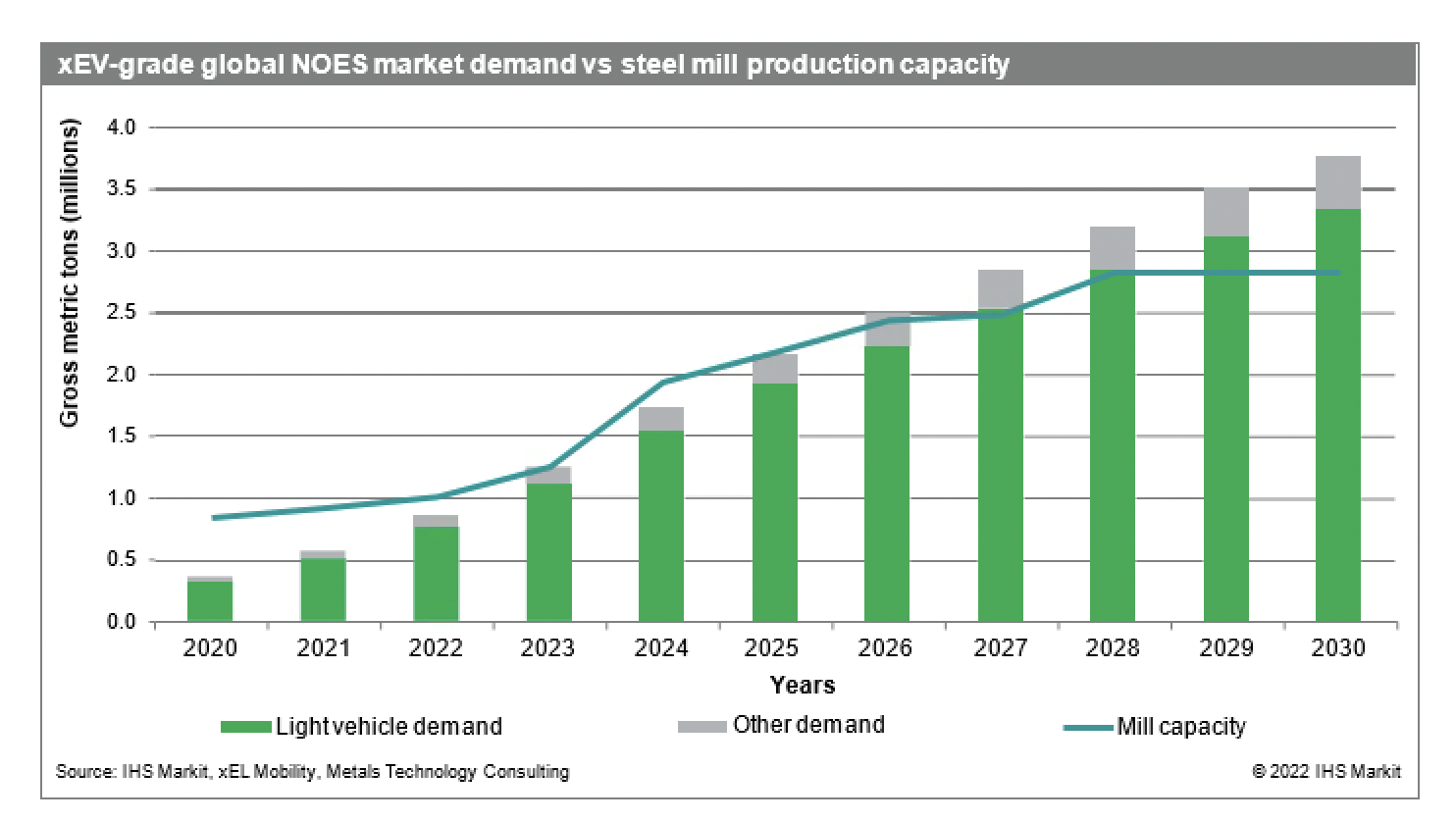

Another area of automotive supply chain concern is electrical steel. Electrical steel is a grade of steel which, for automotive purposes, is used in significant amounts specifically in electric motors for propulsion. Anywhere between $60 to $200 worth of electrical steel goes into electric vehicles. More than two-thirds of the production takes place in China and South Korea— in other words, it’s a very concentrated supply base. There are only 20 manufacturing sites on a global basis that can produce automotive-grade electrical steel, with virtually no capacity in North America. This means that the capacity is already really being stretched as we look out into 2022.

To put this into perspective, even in a worst-case scenario, this won’t be as bad as the chip shortage because the chip shortage has meant that a vast portion of the manufacturers’ portfolio could not be manufactured. Here, we are looking at specific segments of their vehicles that could not be manufactured, particularly battery electric vehicles. But similar to the chip shortage, we’re looking at a structural deficit of electrical steel that needs to be addressed. We may get by in 2022, but as we look out at 2025, 2026, and beyond, a significant structural deficit of these input has begun to emerge, which will require significant investment in capacity. Building this capacity does require time.

The recent experience of these input shortages are forcing automakers to go against everything they have done in the past 30 years when it comes to supply chain management. This means going against the famous Toyota Way, which was predicated upon lean supply and having as little inventory as possible. Carmakers are now considering taking on inventory for certain parts because, in relative terms, it costs peanuts to have that inventory compared with having a line stoppage. A line stoppage costs upwards of $50 million per week to an OEM (original equipment manufacturer), an unpalatable outcome if you’re missing just maybe $500,000 worth of inventory. The crisis is also forcing the OEMs to think differently about their supply chain. For example, there is an argument for automakers to create partnerships with companies with whom they had very limited dealings with only a few months back (or even ignored their existence), be it chip manufacturers or other companies in critical upstream operations. This is a sign of the changes that the supply chain crisis has imposed on the automotive industry.