Compared with a year ago, crude oil, coal, and natural gas are substantially higher, all owing to strong demand that has come with economic rebound. These rising prices are feeding into inflation, and geopolitical risks that could cause further disruptions hang over the market.

Entering 2022, crude oil prices are up about 55% from a year ago at this time. Internationally traded coal prices recently were up 100%. And spot prices for gas in Europe and Asia in early January are 350% higher than a year ago.

That can change by the day or the hour, but that provides a sense of the magnitude of the increase in prices and volatility we’ve seen over the last year.

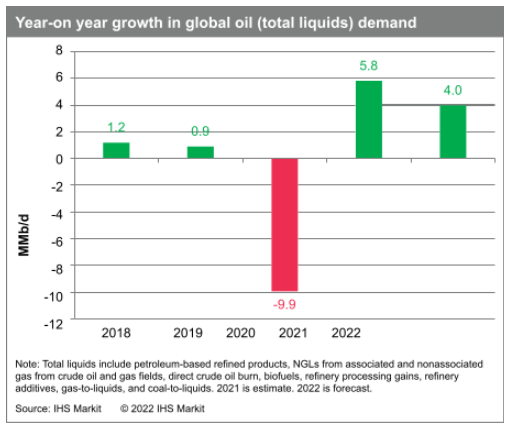

The reason for the spot gas increases in Europe and Asia is pretty straightforward—we’ve had a strong demand push. Third quarter 2021 demand was up about 9% globally. That’s been scraping up against production capacity, which means supply is relatively inflexible in the short term. Coal maxed out, which pushed up gas demand, and the only way to ration that supply is to see these really unanchored gas prices we’ve seen recently. Oil hasn’t gone up nearly as much as liquefied natural gas (LNG), but it’s still up substantially—one reason is the strong demand recovery in 2021 as we saw in so many other sectors. But there’s also spare capacity for oil. We’re not bumping up against spare capacity in oil as we have against LNG and coal. However, there is less spare capacity of crude oil production today—about 3 million barrels per day—compared with a year ago. If there is not significant supply growth from the United States and other sources outside of the OPEC+ agreement in 2022, then spare capacity could shrink further, which will make the oil market more crisis prone.

Regarding Omicron, we do not believe at this point in time that it’s a repeat in terms of oil demand in March and April of 2020, when oil demand globally fell about 20%. You’re not going to have that type of reaction. However, this is clearly a negative for demand. It’s going to hurt jet fuel demand in the short term, in addition to bad weather and airline staffing shortages.

One can come up with varying scenarios. We think at this point that Omicron will cut off about 500,000 barrels per day in first quarter 2022, hitting jet fuel the most. This is in an oil market of close to 100 million barrels per day of consumption, so that’s a relatively modest impact right now. But again, it’s been less than two months since Omicron emerged in South Africa, so it’s still early days in terms of understanding it and its effects, as compared with Delta and the original virus. But it certainly does, as COVID did last year, hit at the heart of oil demand, which is mobility.

High gasoline prices get a lot of attention around the world, especially in the United States where increases are not muffled by high tax rates, as in Europe. There’s always pressure on any US administration, Republican or Democratic, to do “something” about it, and one of the ideas that has been put forth is to ban US crude exports. The United States exports a lot of crude oil—about 3 million barrels per day. Should there be a ban on that to keep it in the country? Will that lower gasoline prices?

The short answers to all these questions is that would make the problem much worse. If you want to make supply chain issues much worse, then implement a crude oil export ban from the United States. It would be a major shock to the global market and would create a new level of supply chain disruptions in the United States.

There’s a number of reasons why it is such a bad idea. One is the gasoline price in the United States is not set by the price of domestically produced crude oil but rather by the global crude oil market price. India, Japan and Korea, the Netherlands—these are allies and partners of the US. If you were to rip out that 3 million barrels per day from the global oil market, what’s going to replace it? Additionally, much of that oil is not really the preferred type of oil that US refineries want. Therefore, an export ban would just introduce a policy that would make the problem worse. And it wouldn’t lower gasoline prices. If anything, it would probably raise them.