Introduction

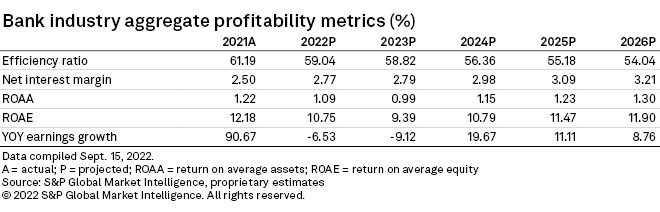

Swift increases in interest rates and strong loan growth will allow banks to record considerable expansion in net interest margins in 2022, but funding pressures should also grow over the coming year.

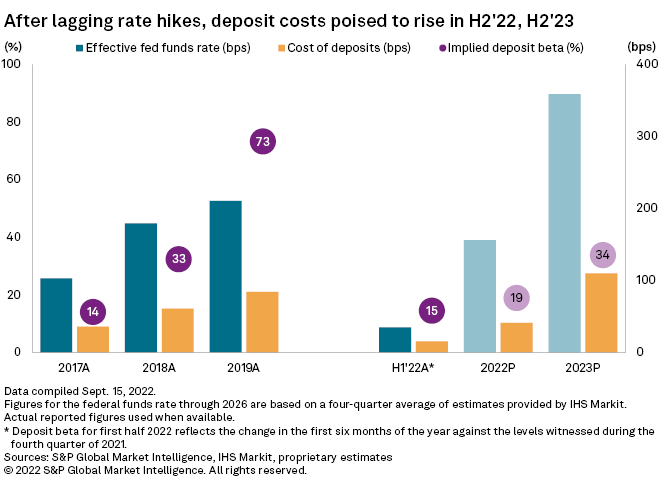

As the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy to tame elevated inflation, banks' margins will expand notably in 2022. Deposit costs have only climbed modestly through the first half of 2022 but will rise more quickly in the second half of the year and increase even further in 2023, slowing margin expansion. Higher rates and elevated inflation have also raised recessionary fears and the prospect of notably higher loan losses. We expect credit costs to normalize in 2023 and prevent earnings from growing from year-ago levels but believe that losses will be manageable.

Higher rates offer lift to margins but pressure on deposit costs rising

The Fed has raised short-term rates by 225 basis points through August and hiked rates by another 75 basis points on Sept. 21, while planning to continue shrinking its balance sheet. Those actions will bolster bank margins and allow the key profitability metric to expand by 27 basis points in 2022 to 2.77%.

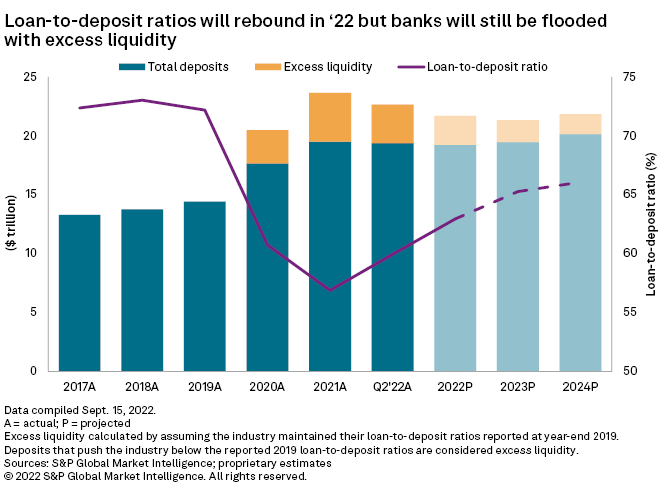

The Fed's balance sheet reduction, elevated inflation and utilization of some of the nearly $2.5 trillion in excess savings that consumers accumulated through the pandemic are expected to put some pressure on deposits, allowing loan-to-deposit ratios to recover from depressed levels. Some of those liquidity pressures emerged in the second quarter when deposits declined 1.9% from the prior period but balances remained above year-ago levels. As elevated inflation and higher rates persist, deposits are now expected to decline modestly in 2022, while loans grow 9%, allowing institutions to deploy more of their excess liquidity to work.

Historic deposit growth during the pandemic left banks sodden with excess liquidity, reaching an estimated $4.13 trillion at year-end 2021. Excess liquidity has declined this year but still stood at $3.28 trillion at the end of the second quarter of 2022. We expect excess liquidity will decline notably in 2022 and drop further in 2023, falling below $2 trillion.

Excess liquidity has weighed on bank margins but has also allowed institutions to slowly increase deposit rates, even as the Fed tightened monetary policy at the quickest pace in 30 years. Most institutions have not increased the rates they offer on many deposit products that much thus far despite sizable increases in short- and long-term rates.

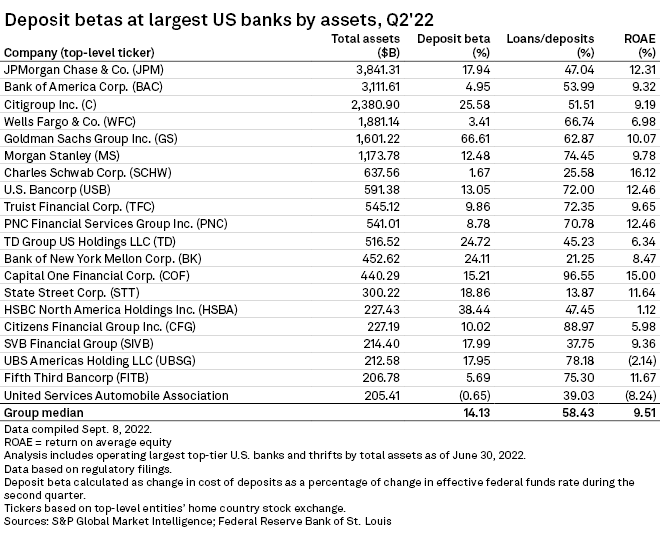

When excluding outlier institutions like The Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and HSBC North America Holdings Inc. — which do not have large retail branch networks and historically have relied on deposits from wealth management, commercial and digital-only clients — the largest banks have not seen much pressure on their deposit rates. In fact, among the top 20 largest banks, the average quarter-over-quarter deposit beta, or the percentage of change in the federal funds rate that banks passed through to depositors, was just 12.6% in the second quarter, when excluding Goldman and HSBC. That is below the level recorded during the first year of the last tightening cycle when the pace of rate hikes was much slower.

We expect deposit betas to accelerate in the second half of 2022 but to remain relatively close to the levels seen during the last rate hike cycle given that institutions continue to operate with historically low loan-to-deposit ratios. With excess liquidity expected to shrink and rates to exceed 3% in 2023, we project the banking industry to record a deposit beta of 34% in 2023, leading to a cumulative beta of 27.6% by the end of 2023.

Normalized credit trends on the horizon

Higher rates should help boost loan yields, but historically low loan-to-deposit ratios should lead to strong competition for new loans. S&P Global Market Intelligence expects the industry's loan yield to increase to 4.50% in 2022 from 4.30% in 2021. Market Intelligence then sees the yield on loans rising to 5.06% in 2023 and 5.30% in 2024.

However, higher interest rates pose a threat to some borrowers and have already caused mortgage origination activity to plunge, resulting in pressure on mortgage banking income. Regulatory pressure and emerging competition from neobanks should also contribute to weaker noninterest income as many institutions have eliminated overdraft fees.

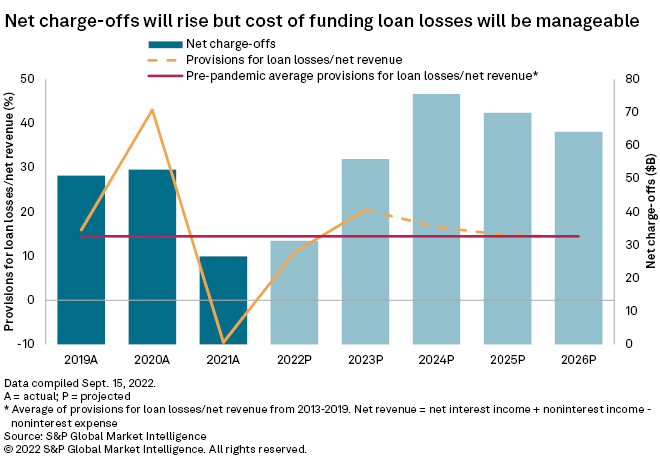

Banks face higher credit costs as well after receiving a huge boost from reserve releases in 2021. Reserves have held fairly steady through the first six months of 2022 even as loans have grown at a fast pace. Reserves should increase modestly in the latter half of the year as elevated inflation and the Fed's efforts to tame it increase the prospect of an economic slowdown and credit deterioration in bank loan portfolios.

Credit deterioration should be more pronounced in 2023 as higher operating and borrowing costs for companies and consumers and slower economic growth take their toll. There are already signs of weakness in the market, with the yield curve inverting, which is often a precursor of a recession. Higher mortgages have slowed the housing market as well. New building permits have fallen to the lowest level in two years, home sales activity has plunged and the months of supply of homes has risen to the highest level in more than a decade.

Banks seem to be preparing for a potential slowdown and indicated in the Fed's most recent senior loan officer survey that they tightened lending standards. However, institutions maintained pristine credit quality through the second quarter, and early credit indicators like criticized loans continued to decline through the second quarter.

Consumer balance sheets also remain strong, with household debt to income levels standing at 9.5% or about 1.5 percentage points below the 40-year average. Consumers have a cushion to fall back on should they need it as they still boast nearly $2.5 trillion in excess savings accumulated during the pandemic. The lack of meaningful loan growth in recent years and banks efforts to scrub their portfolios during the height of the pandemic should also offer institutions some protection and keep loan losses at manageable levels. Should a deep recession materialize, loan losses could prove higher than projected, but bank balance sheets remain well equipped to weather a downturn and a normalization of credit trends.

Scope and methodology

Market Intelligence analyzed nearly 10,000 banking subsidiaries, covering the core U.S. banking industry from 2004 through the first half of 2022. The analysis includes all commercial and savings banks and savings and loan associations, including historical institutions, as long as they were still considered current at the end of a given year. It excludes several hundred institutions that hold bank charters but do not principally engage in banking activities, among them industrial banks, nondepository trusts and cooperative banks.

The analysis divided the industry into five asset groups to see which institutions have changed the most, using historically significant regulatory thresholds. The examination looked at banks with assets of $250 billion or more, $50 billion to $250 billion, $10 billion to $50 billion, $1 billion to $10 billion, and $1 billion and below.

The analysis looked back more than a decade to help inform projected results for the banking industry by examining long-term performance over periods outside the peak of the asset bubble from 2006 to 2007. Market Intelligence has created a model that projects the balance sheet and income statement of the entire industry and allows for different growth assumptions from one year to the next.

The outlook is based on management commentary, discussions with industry sources, regression analysis, and asset and liability repricing data disclosed in banks' quarterly call reports. While taking into consideration historical growth rates, the analysis often excludes the significant volatility experienced in the years around the credit crisis.

The outlook is subject to change, perhaps materially, based on adjustments to the consensus expectations for interest rates, unemployment and economic growth. The projections can be updated or revised at any time as developments warrant, particularly when material changes occur.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.