While operating in one of the so-called hard-to-abate sectors, some major maritime transportation companies have set ambitious climate targets as their decarbonization pathways emerge.

Of the 10 largest shipping companies by market capitalization globally, all have some form of net-zero target, though ambition levels differ. Most want to reach the goal in 2050, in line with what the United Nations says is required to cap global warming at 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels and avoid climate disasters.

In the view of many, including the US government, maritime emissions are hard to curtail because ships deployed to international shipping — which accounts for 2% to 3% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions as they burn oil-based fuels — are generally too large to be powered by batteries.

However, major ship operators have started to embrace a low-carbon transition as new propulsion technologies based on sustainable energy sources, such as green methanol and ammonia, enter the market. The issue is that such fuels are not now widely available.

"It's not hard from a technical perspective, but it is expensive because we need to build the production facilities," said Morten Bo Christiansen, head of energy transition at Danish shipping conglomerate A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S, which has estimated a $2 trillion investment could be needed in green fuels production facilities by 2050 to decarbonize the whole industry.

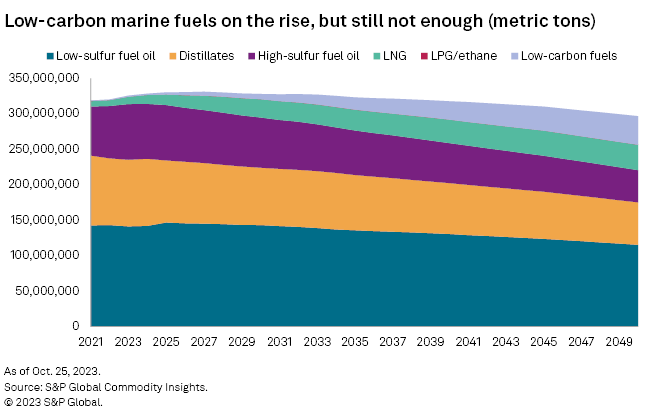

Amir Sokolowski and Vicky Sins, climate experts at CDP and the World Benchmarking Alliance, said such fuels must make up 84% of the total bunker mix by 2050 to align with the Paris Agreement on Climate Change's 1.5-degree C climate target.

Their share was at 0.3% in 2022 and is expected to reach just 14% in 2050 without accelerated decarbonization efforts by governments and businesses, according to S&P Global Commodity Insights analysts.

"Shipping's pathway to net-zero by 2050 relies almost exclusively on the development of low-carbon alternative fuels," they wrote in emailed comments. "Significant investment is needed to make these fuels viable for use at scale."

International goal

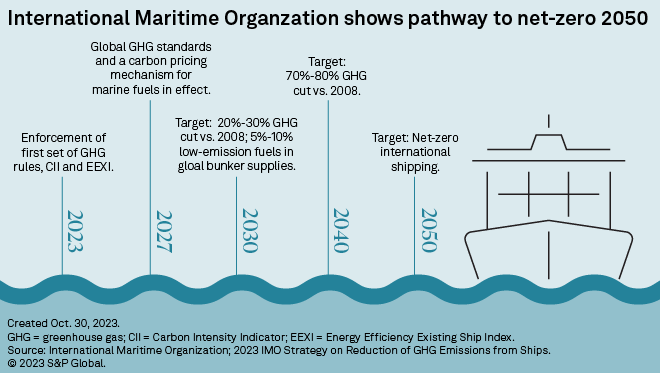

The targets of major shipping companies were mostly set before the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the industry's global regulator, in July tightened the eventual emissions goal for cross-border shipping to net-zero close to 2050 from a 50% cut against 2008 levels previously.

As the UN agency plans to introduce stricter emissions rules from 2027 to decarbonize shipping, observers such as Grace Healy from nonprofit Pacific Environment and Allyson Browne from Ports for People expect that some maritime companies could raise their targets to match or exceed the IMO's ambition.

"However, we won't see meaningful impact towards achieving zero emissions unless and until there is enforcement pressure behind these [IMO] policies," Healy and Browne said in an email, suggesting that voluntary efforts alone might not be sufficient to prompt large-sale investments in low-carbon fuels.

Nishatabbas Rehmatulla, a principal research fellow at the University College London Energy Institute, said companies should base their climate strategies on the Paris Agreement rather than IMO policies.

"Following the IMO to set your own company's decarbonization targets is futile; it will keep changing [upwards] as has been evidenced," Rehmatulla said.

"If companies invest based on each [IMO] revision ... they could be facing risks of stranded assets" that could not meet more stringent IMO regulations in later years, Rehmatulla added.

Divergence

Even among major shipping companies, decarbonization targets range widely based on geographies and sectors.

Maersk aims to reach net-zero emissions across its value chain by 2040 and Hapag-Lloyd AG by 2045. These two companies, which have the most aggressive targets, are both based in the EU, where authorities are leading the world in ushering in shipping emissions regulations in 2024–2025.

"Europe's climate legislation and regulation is ahead of most other regions, showing the impact that tougher regulation can have in encouraging more action from companies," Sokolowski and Sins said.

Conversely, companies controlled by the Chinese government, which has a national target of carbon neutrality by 2060, have lesser ambitions.

Cosco Shipping Holdings Co. Ltd. targets carbon neutrality by 2060, later than major players outside of China. China Merchants Energy Shipping Co. Ltd. aims to reach net-zero CO2 emissions in its domestic operations by 2060 but lacks such a goal for its international business. Cosco Shipping Energy Transportation Co. Ltd. aims to pursue net-zero emissions but is yet to suggest a timeline.

"There are many state-owned shipping companies. ... These companies face different and generally less external pressure for climate action," Healy and Browne said.

Moreover, container shipping companies such as HMM Co. Ltd., Maersk and Hapag-Lloyd generally have more comprehensive targets covering all scopes of emissions and detailed decarbonization strategies that include green fuel usage. Those transporting dry bulk and energy products tend to be less aggressive.

This is because box carriers' clients are often consumer-facing brands that face more pressure from civil society, while others serve traders and industrial companies that could struggle to bypass higher costs associated with low-carbon shipping down the supply chain, according to industry participants.

"The liner sector ... is more visible than other sectors," said John Butler, CEO of the World Shipping Council, an industry association representing liner operators. "A lot of our customers are very visible companies, well-known companies."

Multiple governments and industry stakeholders have been developing collaboration projects that could allow the whole industry to build on container lines' low-carbon capacity. For one, industry group Global Maritime Forum estimates that about 30 green corridor initiatives have been launched since 2021, each promising to raise green fuel supplies from one bunker hub to another.

While those projects are not necessarily sector-specific, container lines could provide stable demand for green fuels with their regular calls. Then, bunker suppliers can scale up to meet requirements from other shipping sectors.

"At the end of the day, the synergies from sending a strong demand signal for these new fuels are more powerful than competition for these fuels," Butler said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights reporter Max Lin produces content for distribution on Platts Connect. S&P Global Commodity Insights is a division of S&P Global Inc.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.