The U.S. energy sector is in the midst of an extended period of transformative change, broadly referred to as the energy transition. Power and gas providers are scrambling to respond to increasing demands from public policymakers, regulators and customers to improve the reliability and resiliency of the grid in the wake of more frequent weather events, while at the same time moving away from carbon-emitting generation and heating resources to renewable and/or zero-emissions resources.

The concept of "stranded costs" is not new to the energy utility industry. Stranded costs are investments made by a utility in good faith and often with the approval of state regulators that later became unneeded, uneconomic or otherwise unviable due to a change in public policy that was outside of the utility's control.

While not dubbed as such, utilities and their regulators have been addressing stranded costs since the 1980s, when unexpectedly stagnating load growth led to several generating units that were under construction being canceled mid-project.

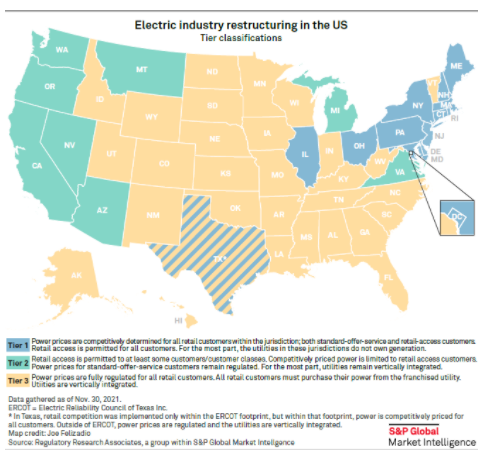

The term "stranded costs" is more closely linked to the implementation of retail competition for generation that occurred in some states during the mid-1990s and early-2000s, when it was thought that legacy-regulated generation facilities would be devalued. Policymakers generally agreed that under the "regulatory compact," the utilities should be compensated for this devaluation, as it stemmed from a change in the regulatory framework.

With the more recent acceleration in the so-called energy transition, stranded cost concerns have arisen again, but with certain differences from the historical experiences. First, the potential for stranded costs has been expanded and is now relevant to additional classes of assets, such as electric and gas distribution. Second, some of the affected assets are merchant or unregulated investments that are outside the purview of state regulators, and therefore, other remediation measures may need to be brought to bear.

How regulators and policymakers address these challenges for both regulated and unregulated entities will be a key component in achieving public policy goals and will have a significant impact on both the financial performance of the entities, subject to their jurisdiction and the level of prices paid by customers.

As the energy transition gained momentum, the aging coal fleet in the U.S. — once the backbone of the utility generation portfolio — has been shrinking. Fifteen years ago, coal accounted for over half of the U.S. generation portfolio. By 2018 that percentage had fallen to 27%. According to data gathered by S&P Global Market Intelligence, as a result of the energy transition, 20 GW of coal-fired generation capacity was retired during 2017 through 2019, and another 29 GW of retirements are planned for the years 2020 through 2025.

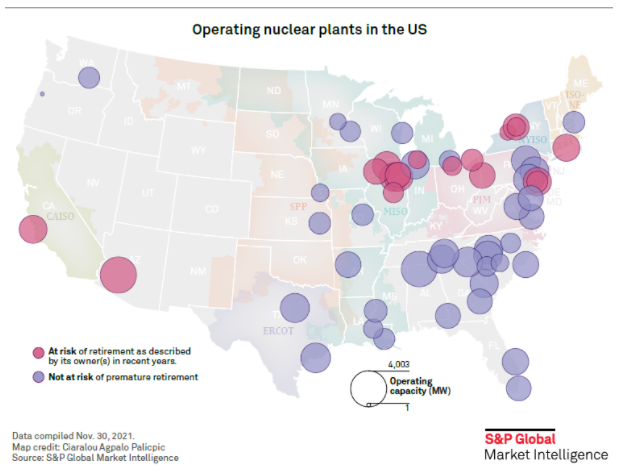

Changing market dynamics and increasing renewables mandates during this transition have also impacted nuclear plants. Since 2013, 12 nuclear plants totaling almost 10 GW have been shut down prematurely.

As the energy transition in the U.S. continues to gather momentum, the potential for stranded investment is increasing across the electric and gas value chain. Classes of generation assets once seen as solutions are now being viewed as problems, investment made to meet previously effective environmental policies is becoming obsolete sooner than expected, and new market configurations and the need to install new technologies to accommodate them presents challenges for the legacy transmission and distribution systems that is raising the specter of stranded costs in those segments of the industry.

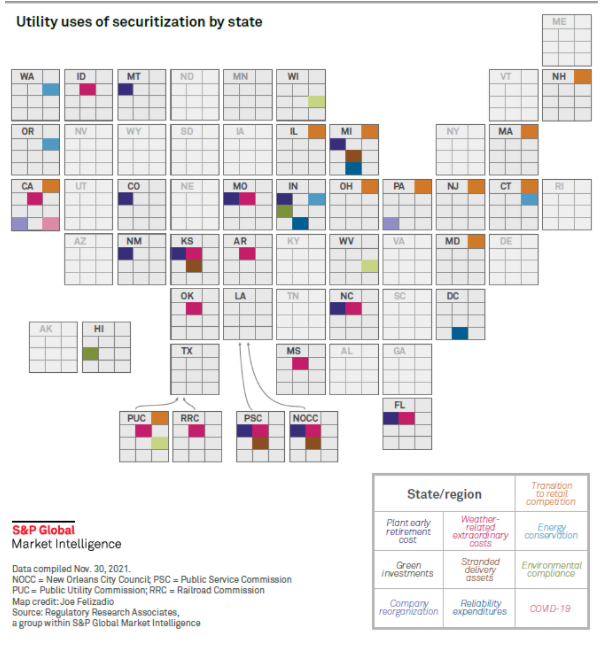

For utilities subject to their jurisdiction, state regulators have various tools to address and/or forestall stranded costs. These include accelerating depreciation of the assets to be retired early, creating regulatory assets that will allow the remaining value of the facilities to be recovered over time and allowing the companies to securitize unrecovered balances in order to reduce the costs to ratepayers of compensating the utilities.

For unregulated or merchant entities, there are fewer options for mitigating stranded costs, but legislators have in recent years introduced some innovative approaches for certain types of generation facilities. For example, a few states have implemented subsidy programs designed to make it more economic for nuclear facilities to continue to operate. There have also been instances where coal-intensive states have implemented policies to support the continued operation of coal-fired generation.

Among the infrastructure upgrades that have been accelerating as part of the energy transition are utility initiatives to replace traditional analog meters with advanced metering infrastructure technology. If the legacy meters being replaced are not fully depreciated when these programs are implemented, the legacy meters may also be considered stranded costs. These are largely regulated investments that are generally eligible for recovery.

Electrification initiatives, i.e., programs to incent or even force a switch to electric home heating in place of traditional oil or gas heating, while localized, are becoming more prominent and are threatening to bring stranded cost concerns to the gas local distribution utilities. These activities are for the time being concentrated in the West and the Northeast. In other areas of the country, legislation has been enacted to prohibit municipalities and local governments from implementing gas bans.

Outlook

Potential stranded costs are among the plethora of issues U.S. utilities, regulators and policymakers will need to address as the energy transition proceeds. U.S. regulators have experience addressing these and similar issues as stranded costs arose during other times of significant transformation. These tools include traditional ratemaking constructs such as accelerated depreciation and the creation of regulatory assets, as well as newer, more innovative approaches such as securitization, which can minimize the impact on ratepayers. The issues are somewhat more complex in this iteration, as stranded costs have arisen and will continue arise across a broader swath of asset classes. Even so, relying on the regulatory compact, utilities will likely be accorded a reasonable opportunity to recover their stranded costs, but the terms of that recovery may be constrained by concerns regarding the ultimate impact on ratepayers. Further complicating matters, some of the entities that will be at risk for owning assets that may become stranded are not subject to the jurisdiction of state regulators and therefore, the aforementioned regulatory tools to address these costs will not be available to them. However, several states have implemented legislative solutions that are providing support to certain key assets to forestall the possibility of them becoming stranded.