S&P Global held a cross-divisional event on Sept. 9 looking into the context, impact and outlook of the U.S.-China trade war. The program included a presentation of Panjiva research of Sept. 5, 2019 as well as a panel discussion moderated by Soumaya Keynes of The Economist. This report provides a paraphrasing of the panel discussion as well as selected data-driven insights from Panjiva.

Q: How bad has the trade war gotten?

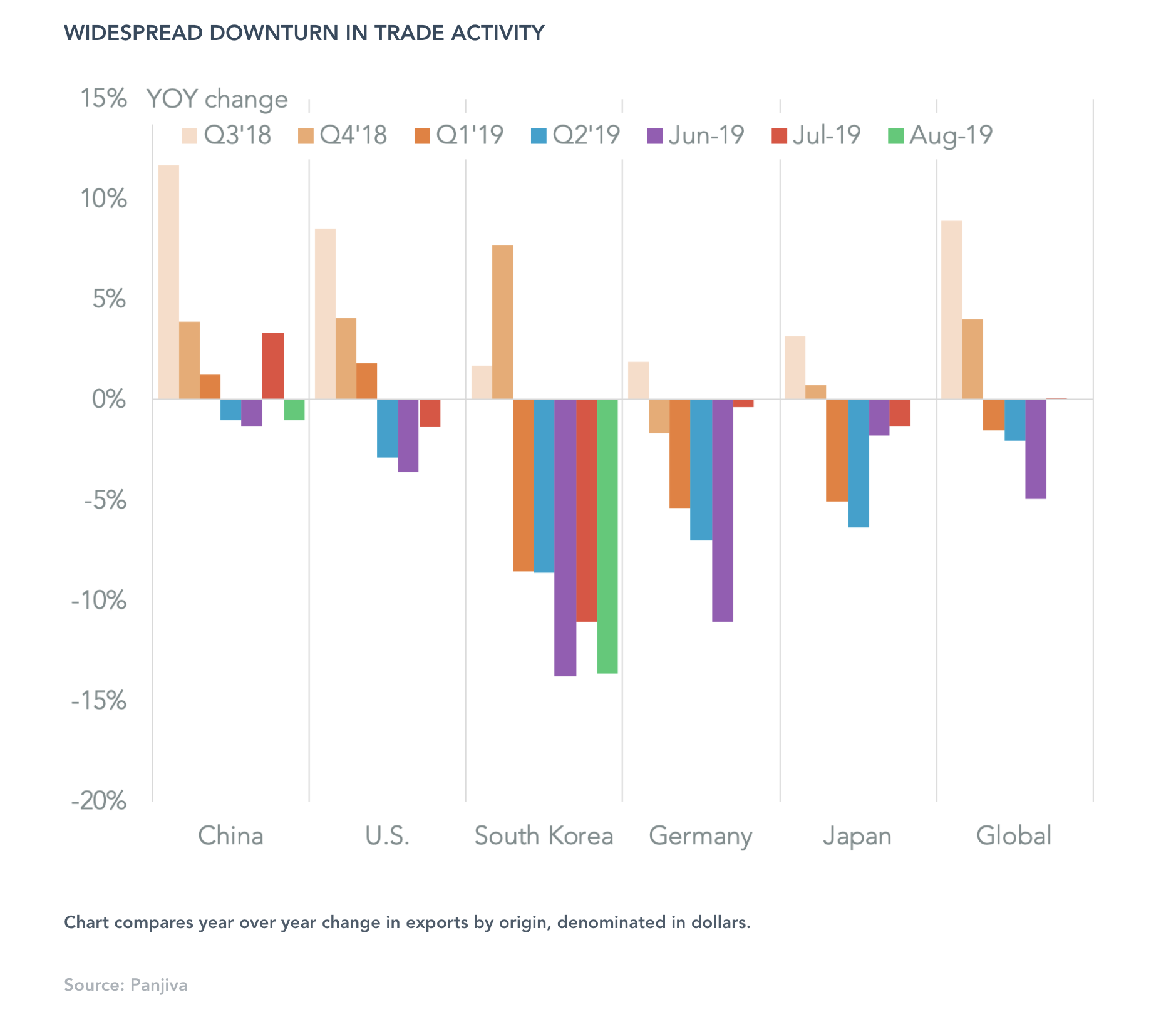

Paul Gruenwald – Chief Global Economist S&P Global Ratings: The situation is certainly worse than it was a year ago, with most of the impact being seen in manufacturing and trade-dependent economies. Germany and South Korea have seen significant slowdowns. We haven’t yet seen a spillover into consumption however, which is the main risk for the economies of the U.S. and China as well as parts of Europe.

Panjiva insight: Global trade entered a technical export recession – two consecutive three month period of lower year over year exports in May. While the weighted average of global exports was unchanged in July, 14 out of 25 countries reported a downturn including a ninth consecutive drop of 0.4% in Germany. August isn’t looking much better – South Korea’s exports dropped by 13.6%.

Q: Have U.S. businesses in China been seeing an impact from the trade war?

Jake Parker – US-China Business Council: The latest UCBC survey has shown that businesses have seen a significant impact with lost sales due to tariffs and due to U.S. companies not being seen as reliable suppliers due to trade policy uncertainties. Chinese companies are somewhat less sophisticated in assessing the risks of being involved in a U.S. Treasury entity listing.

U.S. companies in China are moving their sourcing, cutting margins and restructuring but are not leaving China as they are often there to manufacture in China for the Chinese market. Only around one quarter see China as an export platform.

Indeed, some U.S. companies may move manufacturing for Chinese buyers out of the U.S. to avoid falling foul of entity list risks. A final issue is that visas available for Chinese staff of U.S. companies to visit the U.S. offices of their employers are proving more difficult to get hold of.

Q: Where are we seeing the most disruption to corporate supply chains?

Josh Green – Cofounder S&P Global Market Intelligence Panjiva: In the initial period of the trade war there was a focus in the assessments on a very narrow basis – for example between the relative exposure of different freight forwarders. There’s been a shift now however with the scope of assessment being much more widespread – almost all manufacturing sectors are affected in some way.

Q: Where has the U.S. Congress been during the trade war?

Anne Wall – The Duberstein Group: There’s always been a push and pull between the Executive and Legislative branches in the U.S. It is clear though that the legislative tools available are less useful with the current administration versus previous administration. However, there is a bipartisan agreement of the need to address Chinese practices, but raterh a difference over tactics.

Q: How much of the economic slowdown has been down to the trade war, and how much to other factors?

Gruenwald: First, the economic narrative at the start of 2019 was that economic growth in the U.S. and China would slow, but that was a healthy process given several years of above-average growth. Secondly, the slowdown has come as the nature of risk has changed. Risk as it can be assessed and priced, whereas the trade war has introduced uncertainty about the rules of the game making it difficult to build risk models. The challenge currently is that the uncertainty moves into the real economy – watch the jobs figures as a sign of consumer worries and a downturn risk.

Green: The set of concerns that executives face have changed. Historically it has been business relationships that mattered, then increasingly data-driven decisions came to the fore. More recently though the need to understand political science has increased, and with it an opportunity cost of having less time to consider what customers want and less time for innovation.

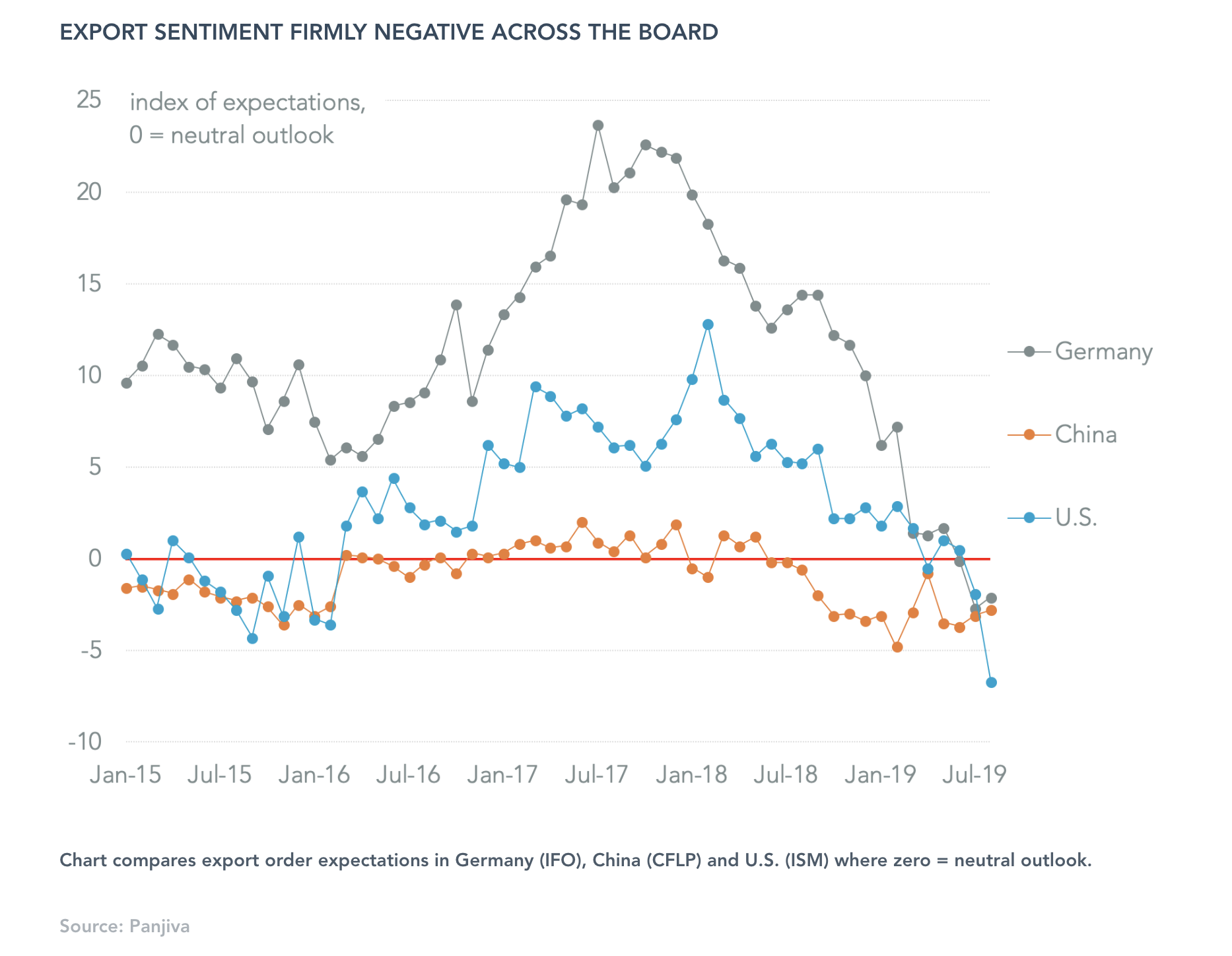

Panjiva insight: The business outlook for export orders has collapsed across the U.S., China and the EU. In the most recent U.S. export expectations survey sentiment fell to its lowest since at least 2010.

Q: The opportunity to remove export restrictions on Huawei was raised at the recent G20 meeting – where is that process up to?

Parker: The G20 agreement was supposed to involve a quid pro quo of Huawei license extensions in return for increased agricultural purchases. There’s yet to be new licenses granted as there is a presumption of denial. For Huawei’s consumer products there should eventually be a continuation of business as usual are there are unlikely to be national security issues. More broadly the conflation of national security and trade issues isn’t healthy.

Wall: Dealing with Huawei is another area of bipartisan agreement – even if the Department of Justice ends its investigation there may be Congressional action.

Gruenwald: On top of the conflation of national security and trade issues the trade war more broadly is a rare example of a major disagreement that has not been mediated through the WTO.

Q: Will we look back at the time of the trade war only be waged through tariffs as being the good times?

Parker: President Trump’s most powerful weapon is the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA), and he has yet to wield it despite threats to do so. That may be limited by the need to clearly articulate, and declare, a state of national emergency on national security grounds. Tariffs applied by China are unlikely to represent such an issue.

Wall: The use of IEEPA may trigger closer oversight and intervention in Presidential decision making by Congress, possibly in the form of legislation.

Green: There’s also a bigger issue as to whether, and how, the U.S. and China can find a way to work together. A recent Panjiva survey indicated that 64% of respondents expect the trade war to continue beyond 2020. If they can’t find a way to work together the outcome may have to be decoupling.

Gruenwald: It’s unlikely that a trade deal can resolve the longer term tensions between the two, which relate to China’s rise as a great power. Economies can grow by adding labour, capital or productivity and China is becoming increasingly reliant on the latter and by extension more reliant on technology from other countries, including the U.S. It’s worth noting though that China has also been driving global growth – a slowdown there will be felt widely.

Parker: Regardless of the political complexion of future administrations, it will be difficult for them to resist the temptation of using tools like tariff for political ends – that becomes an issue for the global, multilateral trading system more broadly. In any event the use of tariffs within trade agreement enforcement leaves residual uncertainty for businesses.

Green: There’s even an issue as to what a stable outcome even looks like. Business executives may become concerned that agreed deals could rapidly come undone, which in turn leads to increased uncertainty.

Gruenwald: There may be signs of the use of tariffs and trade policy in a geopolitical setting becoming the new normal in the instance of South Korea and Japan’s current spat.

Q: Will trade matter for the elections, how easy will it be for the next President to roll back tariffs and will a Democratic administration be more multilateral?

Wall: For the Democrats trade is more an issue of labor than just trade deficits, and we’ve seen the employment issues resulting from the trade war in Iowa already. In general though domestic issues like health care matter more than trade. In terms of rolling back tariffs the next President may be more comfortable in using wide-ranging executive powers than those in the past. In many regards there’s alignment between President Trump and Democratic Party candidates on trade issues – the details are in implementation. There is the possibility of CPTPP coming back under a Democratic administration.

Green: There’s a long history of politicians finding a useful enemy to define themselves against, and that applies to both President Trump and President Xi. One question for the 2020 election season is the extent to which either side sees it as advantageous to maintain the other as an enemy, and therefore withhold an agreement.

Parker: A recent Pew Center survey showed that an increasing number of Americans see China negatively. That may make it more difficult for politicians to take a conciliatory stance running into the elections.

Q: Are there opportunities arising from the current situation?

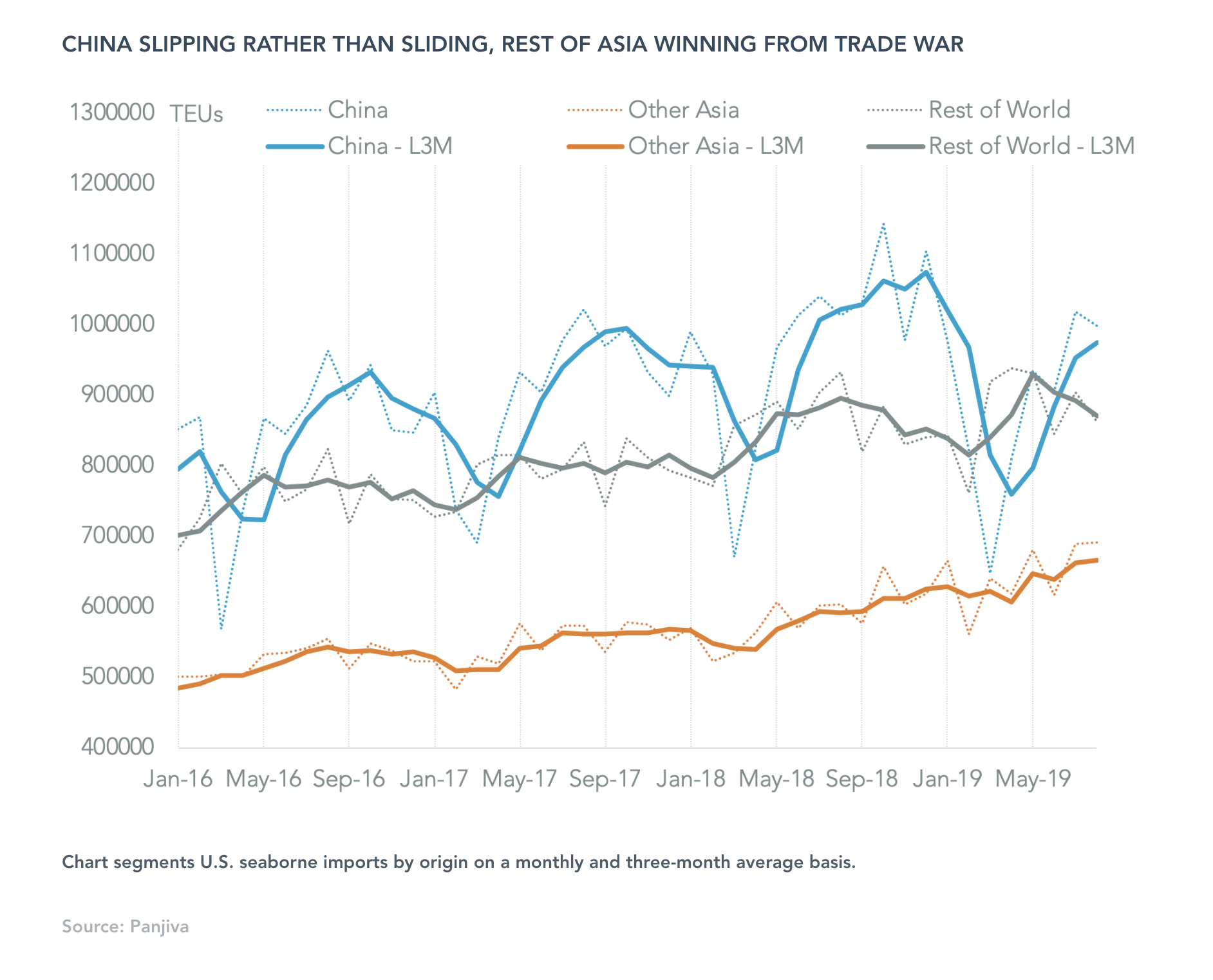

Green: The trade data shows Vietnam has been a clear winner in terms of increased exports to the U.S. Yet, companies who make an early move run the risk that if there’s a deal in the near-term between the U.S. and China then they may have left themselves at a competitive disadvantage. The resulting uncertainty could become a paralyzing issue for corporate investment.

Panjiva insight: There’s been a switch in imports to the U.S. away from China and towards other countries. Panjiva’s seaborne shipping data for the three months to Aug. 31 shows that imports of containerized freight from China fell by 4.7% year over year, or 143k TEUs whereas imports from the rest of Asia including India increased by 12.6%, or 224k TEUs.

Q: Will equity markets treat the current trade uncertainty as the new normal?

Gruenwald: Markets are information processing machines that try to separate signal from noise, and there’s certainly been a high level of volatility. Yet, from a fundamental perspective it is Chinese consumers that have been driving growth and so are a more important measure of the outlook for the economy.

Q: What are the prospects for the Chinese “unreliable entities” list?

Parker: There’s been no in depth details provided by the Chinese government since the original announcement by the Ministry of Commerce in late May. Yet, the impact could be similar to the social credit blacklist with “unreliable” firms facing restrictions to procurement, restrictions to trade or investment, and reduced access to licensing and regulatory approvals.

Q: Are there concerns about rising distrust of Chinese companies in the U.S.?

Parker: So far greenfield investments in the U.S. by Chinese firms still appear to be welcome. However, there is increased oversight of acquisitions under CFIUS, reducing the potential for financial investments.

Wall: The drive for what Chinese companies can invest in within the U.S. is coming from Congress. The main issue is that companies need clear rules of the road, whatever they are.

Q: What are leading indicators to watch for recession, is trade activity something to watch?

Gruenwald: HIstorically investment has been a leading indicator and activity in that regard has been weak. The labor market has been holding up, but a weakening would be a sign of slower economic growth to come.

Q: Should Chinese companies do more lobbying, or is it just politically bad for Congressman to be pro China?

Wall: It is always important to have conversations with elected officials whether you have good or bad news to impart. Even if there is a disagreement you have a chance to be heard and to try and change views at the margins.

Parker: There appears to be a degree of misunderstanding in the U.S. government of China’s motivations, with an apparent view that it is an existential threat. Realistically, China’s goals are regional at best and it does not appear to be interested in replacing the multilateral system with socialism.

Wall: It is worth noting that Hong Kong is becoming an increasing issue for Democratic Party candidates and could be a complication.

Q: Will China’s holdings of U.S. treasuries come into play?

Gruenwald: We’ve seen discussion of the weaponisation is tariffs, so the same consideration about Treasury holdings seems logical. However, demand is high for U.S. Treasury bonds as a source of risk free credit – note how low yields are despite widespread concerns about the deficit.

Q: How optimistic are you about the future?

Parker: China is not going away and there needs to be an accommodation of China’s growth. The Trump administration likely wants to change China now before it gets too big to influence in the future. It appears China is more sensitive to concerns about its practices in the past, so there may be room for change. Chinese growth has always been exposed to external factors – if other countries join the U.S. then change could be accelerated.

Green: We believed at the start of 2019 that there is a deal to be done. Right now though there are questions as to whether the leaders of the two states see a deal as being in their best interests. It’s perhaps a 50:50 chance on each side, so a 25% chance in total.

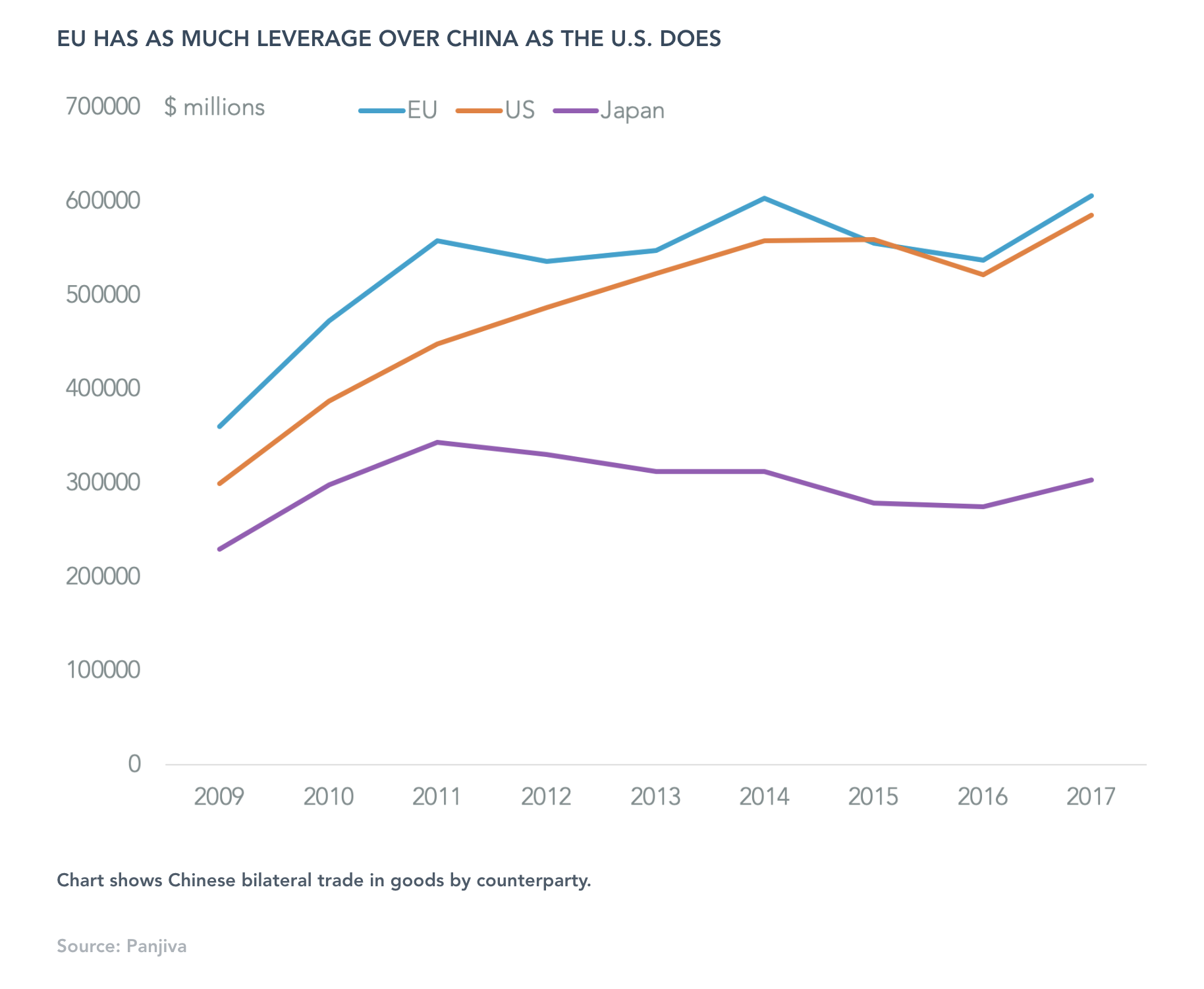

Gruenwald: There’s a good scenario that see the U.S. pivot away from tariffs and moves to improve relations in technology, ease of business and become more multilateral. However, that requires Europe and Japan to be a part of the solution – Europe is a bigger trade counterparty with China than the U.S.

Wall: Things will only get harder as we get closer to presidential elections – sadly as we move past the passage of appropriations bills it seems likely little new legislation will get passed in an election year.

Panjiva insight: The U.S. accounted for 21.7% of China’s exports in 2017 excluding Hong Kong but only 15.8% of its bilateral trade, whereas the EU accounted for 16.4% and Japan for 8.2%.